Viagra gibt es mittlerweile nicht nur als Original, sondern auch in Form von Generika. Diese enthalten denselben Wirkstoff Sildenafil. Patienten suchen deshalb nach viagra generika schweiz, um ein günstigeres Präparat zu finden. Unterschiede bestehen oft nur in Verpackung und Preis.

Umc.br

Support Care Cancer (2011) 19:1069–1077DOI 10.1007/s00520-011-1202-0

A systematic review with meta-analysis of the effectof low-level laser therapy (LLLT) in cancer therapy-inducedoral mucositis

Jan Magnus Bjordal & Rene-Jean Bensadoun &Jan Tunèr & Lucio Frigo & Kjersti Gjerde &Rodrigo AB Lopes-Martins

Received: 26 August 2010 / Accepted: 30 May 2011 / Published online: 10 June 2011# Springer-Verlag 2011

Results We found 11 randomised placebo-controlled trials

Purpose The purpose of this study is to review the effects

with a total of 415 patients; methodological quality was

of low-level laser therapy (LLLT) in the prevention and

acceptable at 4.10 (SD±0.74) on the 5-point Jadad scale. The

treatment of cancer therapy-induced oral mucositis (OM).

relative risk (RR) for developing OM was significantly (p=

Methods A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised

0.02) reduced after LLLT compared with placebo LLLT (RR=

placebo-controlled trials of LLLT performed during chemother-

2.03 (95% CI, 1.11 to 3.69)). This preventive effect of LLLT

apy or radiation therapy in head and neck cancer patients.

improved to RR=2.72 (95% CI, 1.98 to 3.74) when onlytrials with adequate doses above 1 J were included. For

J. M. Bjordal (*)

treatment of OM ulcers, the number of days with OM grade 2

Centre for Evidence-Based Practice,

or worse was significantly reduced after LLLT to 4.38 (95%

Bergen University College-HiB,

CI, 3.35 to 5.40) days less than placebo LLLT. Oral mucositis

Moellendalsvn. 6,

severity was also reduced after LLLT with a standardised

5009 Bergen, Norwaye-mail:

[email protected]

mean difference of 1.33 (95% CI, 0.68 to 1.98) over placeboLLLT. All studies registered possible side-effects, but they

were not significantly different from placebo LLLT.

Service d'Oncologie Radiothérapique,

Conclusions There is consistent evidence from small high-

CHU de Poitiers, BP 577, 86021 Poitiers Cedex, France

quality studies that red and infrared LLLT can partly prevent

development of cancer therapy-induced OM. LLLT also

Grängesberg Dental Clinic,

significantly reduced pain, severity and duration of symp-

Grängesberg, Sweden

toms in patients with cancer therapy-induced OM.

L. FrigoUniversity of Cruzeiro do Sul,

Keywords Low-level laser therapy. Oral mucositis .

Sao Miguel Paulista, SP, Brazil

Cancer. Chemotherapy. Radiation therapy

K. GjerdeDepartment of Clinical Odontology, University of Bergen,Bergen, Norway

R. A. Lopes-Martins

Oral mucositis (OM) is a serious and acute side-effect for

Institute of Biomedical Sciences, University of São Paulo (USP),

patients undergoing cancer therapy. The frequency of its

São Paulo, Brazile-mail:

[email protected]

appearance varies with therapy and cancer type up to 100%in oral cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy or

R. A. Lopes-Martins

radiotherapy [, ].

Centro de Pesquisa Clínica em Biofotônica Aplicada às Ciências

OM has great impact on a patient´s well-being. It may

da Saúde, Universidade Nove de Julho,São Paulo, Brazil

necessitate modifications of treatment planning, suspension

Support Care Cancer (2011) 19:1069–1077

recommended in treatment guidelines [, Recommendednonpharmacological treatments are oral care with mouthrinse] and cryotherapy []. The latter may also be used for theprevention of OM occurrence. Pharmacological agents havelargely been used for palliative care and pain relief, and someare recommended by consensus in spite of lacking scientificevidence from randomised controlled trials. These pharma-cological agents include patient-controlled analgesia withmorphine in transplant patients with hematological malig-nancies and topical anaesthetics like lidocaine alone, or incombination with diphenhydramine []. More recently,pharmacological focus has been directed towards theprevention of ulceration and the drug palifermin, a humankeratinocyte growth factor that stimulates the prolifer-ation, migration, and differentiation of epithelial cells and isrecommended in patients undergoing stem cell transplanta-tions. In addition, amifostine is thought to inhibit harmfulreactive oxygen species release but the scientificevidence for this drug is sparse. More recently, pharmaco-logical focus has been directed towards the prevention of

Fig. 1 Quorum flow chart showing the stages of the reviewing

ulceration (palifermin and amifostine) but no single inter-

process and the number of studies filtered out at each stage

vention yet serves as a panacea for all phases of OM.

Low-level laser therapy (LLLT) is a local application of a

of therapy, need for opioid analgesics, and/or require enteral

monochromatic, narrow-band, coherent light source. LLLT is

or parenteral nutrition with an impact on patient's survival

recommended as a treatment option for OM in the MASCC

]. The additional cost of OM treatment for cancer

guidelines but with limitations due to heterogeneous laser

patients can be considerable [].

parameters and a lack of dosage consensus in the LLLT

Many interventions have been used in OM management,

literature. The action of LLLT is disputed, but a cytoprotective

but only a handful of interventions have sufficient scientific

effect before and during oxidative stress has been observed

support from positive results in controlled clinical trials to be

after pre-treatment with LLLT There is some support

Table 1 Trial characteristics

First column identifies trial by first author's last name and the publication year. Other columns represent: sample size (type of cancer therapy),laser wavelength in nm, laser output in mW, spot size in cm2 , dose in Joules, irradiation time per point, outcomes reported including mucositisseverity scales (WHO or OMI), pain and duration of OM in days and dichotomized overall results given by: (+) significantly in favour of LLLT or(−) non-significant between LLLT and placebo

Support Care Cancer (2011) 19:1069–1077

Table 2 Trial methodological quality scored with an "x" if the methodological criterion is fulfilled

Withdrawals handled

The first column identifies each trial by first author's last name and last two digits of the publication year. The total methodological score (Jadadscale max. score=5) for each trial is given in the last column

for this protective LLLT effect in humans too ], and a

as advised by Dickersin et al. [] for randomised

possible therapeutic window has also been identified for an

controlled clinical trials. Keywords were: low-level laser

anti-inflammatory effect of red and infrared LLLT ].

therapy, low-intensity laser therapy, low-energy laser ther-

Evidence-based treatment guidelines have been forwarded

apy, phototherapy, HeNe laser, IR laser, GaAlAs, GaAs,

from the World Association for Laser Therapy (WALT)

diode laser, NdYag, oral mucositis, and cancer. Hand

searching was also performed in national physiotherapy

doses of LLLT have been identified for osteoarthritis [],

and medical journals from Norway, Denmark, Sweden,

tendinopathies [], and neck pain With the increasing

Holland, England, Canada, and Australia. Additional

body of randomised controlled trials, there seems to be a

information was gathered from LLLT researchers in the

need for systematically reviewing the literature and quantify

possible LLLT effects of LLLT in both prevention andtreatment of cancer therapy-induced OM.

Inclusion criteria

The randomised controlled trials were subjected to the

Materials and methods

following six inclusion criteria:

Literature search

1. Diagnosis: oral mucositis in cancer patients induced

after chemotherapy or radiation therapy

A literature search was performed on Medline, Embase,

2. Treatment: LLLT with wavelengths of 632–1,064 nm,

Cinahl, PedRo, and the Cochrane Controlled Trial Register

treating the mucosa of the oral cavity

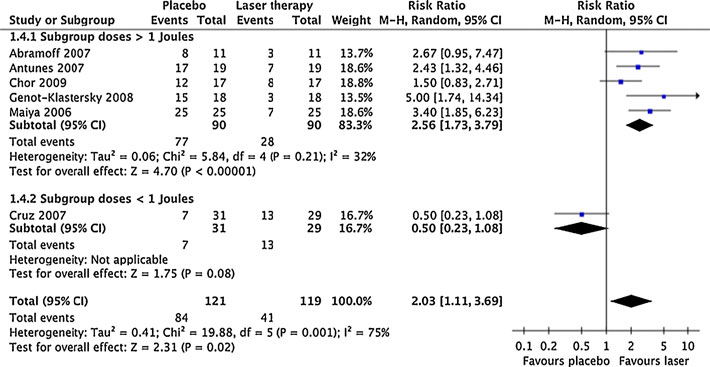

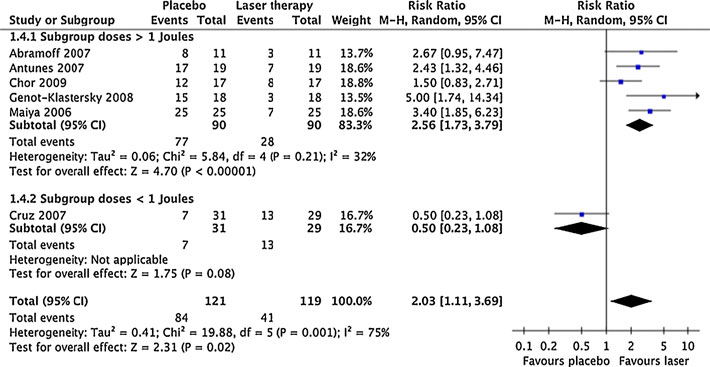

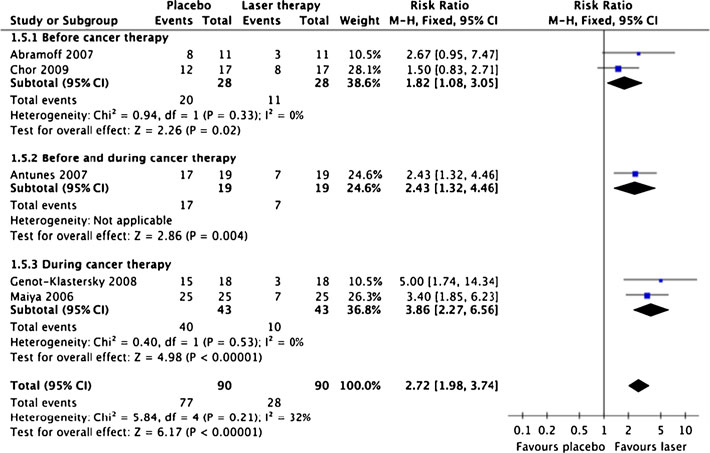

Fig. 2 Forest plot showing themeta-analysis results forprevention of OM occurrence byLLLT dose compared withplacebo. Trial results plotted onthe right-hand side indicateeffects in favour of LLLT, andthe combined effects are plottedas black diamonds for dosesabove 1 J, below 1 J and overallregardless of dose, respectively

Support Care Cancer (2011) 19:1069–1077

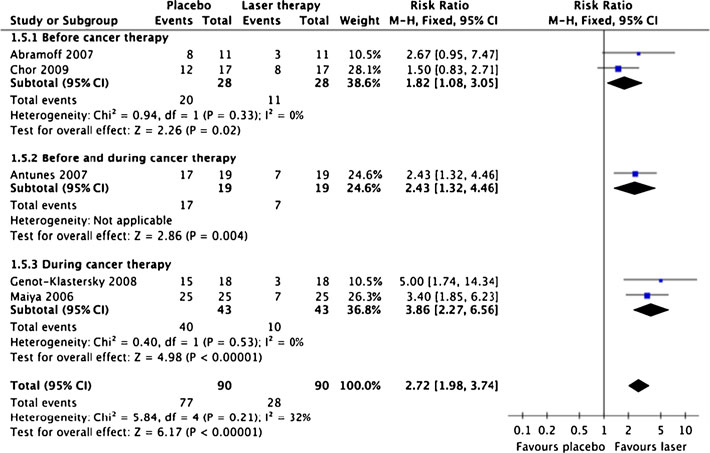

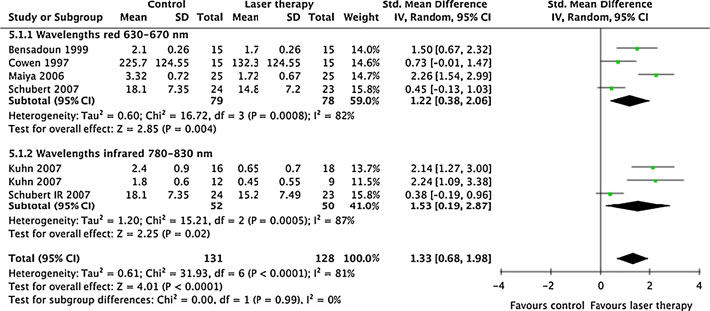

Fig. 3 Forest plot showing themeta-analysis results forprevention of OM occurrence byLLLT wavelengths comparedwith placebo. Trial resultsplotted on the right-hand sideindicate effects in favour ofLLLT, and the combined effectsare plotted as black diamondsfor red wavelengths(630–670 nm), infraredwavelengths (780–830 nm), andoverall regardless ofwavelength, respectively(published online only)

3. Design: randomised parallel group design or crossover

5. Subgroup analyses were planned for (1) doses of <1 J

and >1 J (minimum dose according to WALT guidelines

4. Blinding: outcome assessors should be blinded

for other inflammatory conditions), (2) red and infrared

5 Control group: receiving identical placebo laser

wavelengths with their anticipated optimal dose ranges

6. Specific endpoints for prevention of oral mucositis

(1–4 J for red wavelengths and 3–8 J for infrared

above a certain grade, oral mucositis severity, duration

in days, and pain intensity

A statistical meta-analysis software package developed

by Cochrane Collaboration (Revman 5.0.22) was usedfor the statistical calculations. If heterogeneity was

1. The relative risk (RR) over placebo for preventing

present in heterogeneity tests, a random effects model

occurrence of oral mucositis above a certain grade (0–

was used for calculations. If heterogeneity was absent, a

fixed effects model was used for calculation of the overall

2. The effect of LLLT on the severity of oral mucositis

measured by the Oral Mucositis Index (OMI) or WHOscales were calculated as the SMD versus placebo.

Analysis of bias, including methodological quality, funding

3. The effect of LLLTon the duration of days oral mucositis

source, and patient selection

was calculated as the weighted mean difference versusplacebo

Positive bias direction, caused by flaws in trial

4. The effect of LLLT on pain intensity was calculated as

methodology, funding source

the standardised mean difference (SMD) versus placeboand labelled after Cohen [as "poor" (0.2–0.5),

Trials were subjected to methodological assessments by the

"good" (0.5–0.8), or "very good" (>0.8)

5-point Jadad checklist [For-profit funding sources

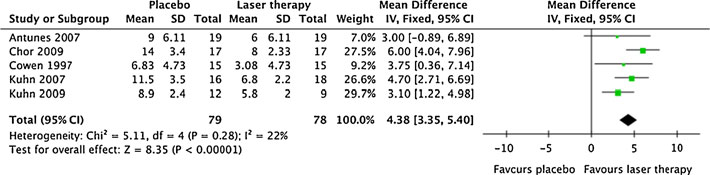

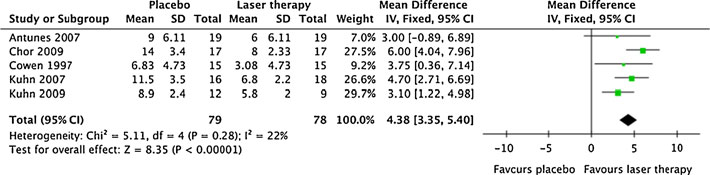

Fig. 4 Forest plot showing the meta-analysis results for duration of

LLLT, and the combined effect including variance is plotted as a black

OM after LLLT compared with placebo as a weighted mean difference.

diamond at the bottom of the forest plot

Trial results plotted on the right-hand side indicate effects in favour of

Support Care Cancer (2011) 19:1069–1077

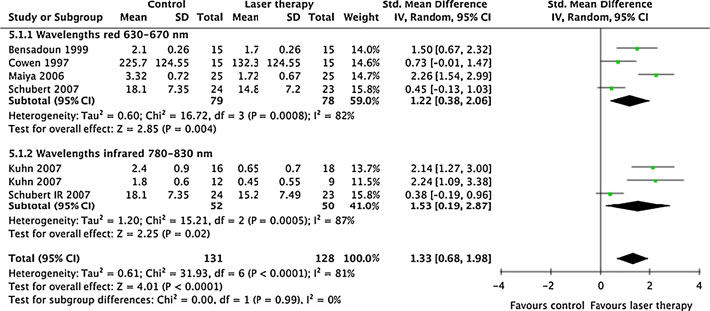

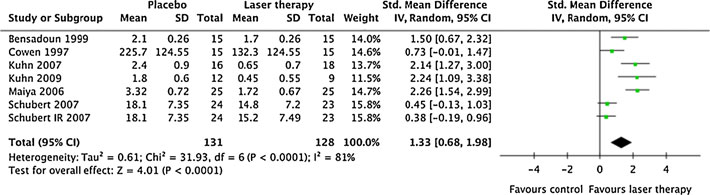

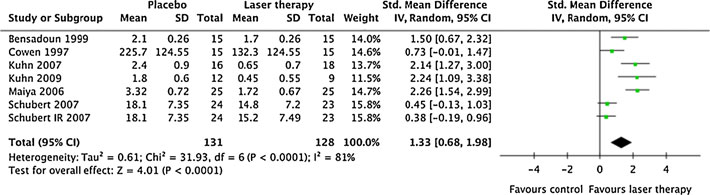

Fig. 5 Forest plot showing the meta-analysis results for LLLT effect

results plotted on the right-hand side indicate effects in favour of

on OM severity compared with placebo as a standardised mean

LLLT, and the combined effect including variance is plotted as a black

difference (combines results from different OM severity scales). Trial

have been shown to affect trial conclusions in a positive

severity. The characteristics of the included trials and laser

direction [which made us include an analysis of

parameters are listed in Table .

funding sources. Methodological assessments were madeindependently according to the Jadad 5-point scale by two

Methodological quality

of the authors (JMB and RABLM).

The assessors gave similar methodological gradings for allthe included studies, and a consensus meeting was not

needed. Methodological quality was high for the includedstudies with a mean score of 4.10 (SD±0.74). The

Literature search and exclusion procedure

individual method scores are given in Table .

The literature search revealed 149 papers for oral mucositis

Funding sources analysis

and laser therapy. Thirty-three were regarded as potentiallyrelevant papers. Of these, nine studies were reviews and six

Laser manufacturers were acknowledged for support in two

studies were case studies while another three were animal

trial reports [One trial report explicitly stated that

studies. Three controlled studies were excluded for lack of

no conflicts of interest existed ] while another trial stated

randomization while one study lacked a placebo-control

that funding came from an independent non-profit source

group ]. The exclusion/inclusion procedure is described

]. Six trials did not explicitly mention conflicts of

according to the ] Quorum standard in Fig.

interest in their trial reports. But none of the affiliations and

The final sample consisted of 11 randomised placebo-

addresses in these reports indicated industry involvement.

controlled trials published from 1997 until 2009 with a total

Double checking the "Instructions to Authors" in the

of 415 patients []. The OMI was used in seven trials

journals in which these trial reports appeared, revealed that

and the WHO was used in one trial as measures of OM

the journals demanded declarations from the authors about

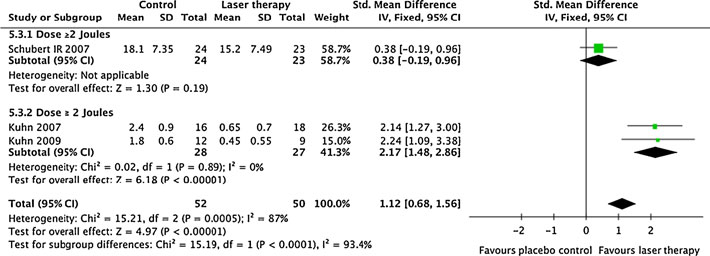

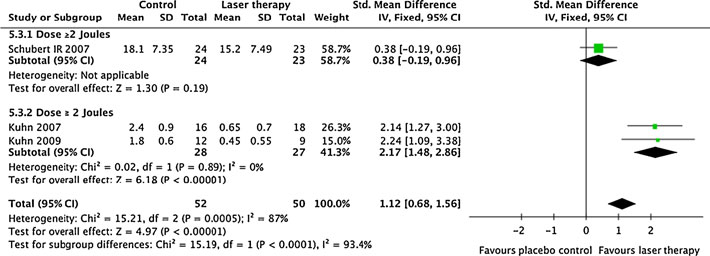

Fig. 6 Forest plot showing the subgroup meta-analysis results for

right-hand side indicate effects in favour of LLLT, and the combined

infrared LLLT doses of ≤2 J or >2 J of the effect on OM severity

effect including variance is plotted as a black diamond (published

compared with placebo as a standardised mean difference (combines

results from different OM severity scales). Trial results plotted on the

Support Care Cancer (2011) 19:1069–1077

Fig. 7 Forest plot showing the meta-analysis results for LLLT effect

the right-hand side indicate effects in favour of LLLT, and the

on pain compared with placebo as a standardised mean difference

combined effect including variance is plotted as a black diamond

(combines results from different pain scales). Trial results plotted on

(published online only)

possible conflicts of interest before publication. For this

Effect on duration of oral mucositis

reason, the lack of mention has been accepted by theauthors as a lack of conflicts of interest, rather than

Five studies presented data for this outcome, and LLLT

undeclared conflicts of interest. In total, bias from for-

reduced significantly the number of days with oral

profit funding sources occurred in just two of 11 papers

mucositis grade 2 or worse with 4.38 (95% CI, 3.35 to

which the authors consider has negligible influence on the

5.40) days. The results for each individual study and the

review conclusion.

combined results are summarised in Fig.

Relative risk for occurrence of cancer therapy-induced OM

Effect on mucositis severity

Six trials presented seven different comparisons of contin-

Six studies started LLLT before OM ulcers occurred and

uous data for mucositis severity. As the trials used different

presented categorical data for the risk of developing OM

mucositis index scales, the combined results were calculat-

above a certain grade (OM grades 0, 1, 2) during cancer

ed as the SMD. The combined SMD effect size was 1.33

therapy. There was a significant preventive effect of LLLT

(95% CI, 0.68 to 1.98) and heterogeneity was present (p<

with a relative risk at 2.03 (95% CI, 1.11 to 3.69) less for

0.0001 and I2=81%). The results for each trial and the

cancer therapy-induced OM to occur. The analysis revealed

combined effect size are presented in Fig.

significant heterogeneity (I2=54%, p=0.03) between trials,and the results are summarised in Fig.

Dose analyses of anticipated optimal dose ranges

Analysis of irradiation parameters revealed that one

study ] had given a lower dose (0.18 J) than theminimum recommended WALT dose of 1 J. After sub-

A subgroup analysis of anticipated optimal dose ranges for red

grouping trials with doses above 1 J, heterogeneity

and infrared wavelengths on OM severity, revealed that

disappeared (I2=16%, p=0.31). The relative risk for

infrared wavelengths (6 J in both trials) gave an SMD at 2.17

preventing OM to occur increased to 2.72 (95% CI, 1.98

(95% CI, 1.48 to 2.86) without signs of heterogeneity between

to 3.74). The results for each study subgrouped by their

trials (I2=0% and p=0.89). A dose of 2 J with an infrared

timing of LLLT subgroups and the total RR are presented

wavelength was ineffective SMD 0.38 (95% CI, −0.19 to

0.96) in reducing mucositis severity. The dose analyses arepresented in Fig.

Subgroup analysis of LLLT wavelength effectson the relative risk for occurrence of OM after LLLT

Effect on pain relief

The subgroup analysis revealed no heterogeneity between

Four trials reported continuous data on pain intensity from

trials with anticipated optimal doses for the red (630–

different scales. The combined analysis revealed a signif-

670 nm) and the infrared (780–830 nm) subgroups,

icant effect of LLLT with an SMD at 1.22 (95% CI, 0.19 to

respectively (p>0.21 and I2<32%), and there were no

2.25) but also significant heterogeneity caused by one trial

significant wavelength differences in relative risks between

]. Removal of this study restored homogeneity (I2=0%

red and infrared at 2.72 (95% CI, 1.98 to 3.74) and infrared

and p=0.58), but reduced the effect size to 0.61 (95% CI,

at 3.48 (95% CI, 1.79 to 6.75).

0.29 to 0.94) (see Fig. ).

Support Care Cancer (2011) 19:1069–1077

Table 3 Summarised recommended treatment parameters

Minimum no. days to start

LLLT before cancer therapy

Side effects of LLLT

previous studies found no significant differences betweenred wavelengths in this range ]. For infrared wave-

All the studies investigated possible side-effects, but none

lengths, 830 nm was used in all trials but one underdosed

found side-effects or adverse effects beyond those reported

trial []. Doses were also fairly consistent across trials

for placebo LLLT. Five trials reported explicitly that LLLT

ranging from 1 to 6 J except the underdosed trial finding

was well tolerated among patients.

no significant effect from a dose 0.18 J. Treatment timesper point varied considerably with the variation in laseroutputs, but at least 17 s of irradiation per point was need

to achieve beneficial results (median, 50 s). The number oftreatment session varied from 3 to 30 in this material, but

This systematic review has revealed moderate to strong

this heterogeneity must be seen in conjunction with the

evidence for the efficacy of LLLT in cancer therapy-

heterogeneity in durations of chemotherapy and radiation

induced OM. A possible limitation to our findings is the

therapy regimens. Our interpretation is that LLLT needs to

small sample size of the included trials. Our finding is

be performed at least every other day for the duration of

partly contradicting a Cochrane review [] which was

chemotherapy and radiation therapy regimens, or as long

recently updated [Our review deviates from their

as OM ulcers are present. The trials which aimed at the

conclusions because we have included more studies and

prevention of OM started LLLT at 7 days before chemo-

subgroup analyses by dose range and wavelengths. The

therapy/radiation therapy regimens. It should be a target

overall scientific quality of the trials was methodologically

for future trials to compare treatment start at different

acceptable, but the heterogeneous treatment procedures

timepoints before cancer therapy to avoid unnecessary

and dosing may cause confusion. In the MASCC guide-

lines, the evidence behind LLLT is characterized as

From the evidence, we propose a fairly simple procedure

promising, but it is added that conflicting evidence with

for diode lasers for prevention and treatment of cancer

large operator variability and expensive equipment (gas

therapy-induced OM. LLLT should be performed with a red

lasers) limits more widespread clinical use []. The lasers

or infrared diode laser with outputs of 10–100 mW in a

used in the studies reviewed are relatively inexpensive

stationary manner (not scanning). The parameters are

diode lasers (from $2,500) with low optical outputs (10–

summarised in Table .

100 mW), which have substituted the older more expen-

In manifested OM, lesions and inflammatory areas

sive gas lasers from the early LLLT trials [After

should be specifically targeted for irradiation. Our

reviewing the apparent discrepancies of the material, our

findings relate well to the emerging LLLT evidence of

subgroup analyses revealed plausible causes for the few

optimal doses in inflammatory conditions such as

conflicting results. A common misunderstanding in the

rheumatoid arthritis [] and acute postoperative pain

LLLT literature is caused by reporting clinical doses for

]. It is also interesting to note that the variety of

diode lasers with small spot sizes in Joules/cm2 rather than

different cancer therapies involved in the included trials

in Joules. If the spot size is very small, then the irradiation

did not seem to seriously interfere with the beneficial

time will be very short. This led to under-dosing in one of

effects of LLLT. How LLLT efficacy compares with the

the included trials, where they irradiated for 3 s per point

efficacy of pharmacological agents in OM, is outside the

WALT recommends that doses in clinical studies

scope for this review but this should certainly be a topic for

should be reported in Joules instead of Joules/cm2. LLLT

future research. In terms of side-effects, LLLT was well

wavelengths and doses were fairly homogeneous in the

tolerated and no serious incidents or withdrawals due to

other studies. Red wavelengths from 633 to 685 nm, and

treatment intolerance were reported.

Support Care Cancer (2011) 19:1069–1077

9. Lalla RV, Sonis ST, Peterson DE (2008) Management of oral

mucositis in patients who have cancer. Dent Clin North Am52:61–77, viii

We conclude that there is moderate to strong evidence in

10. Elting LS, Shih YC, Stiff PJ, Bensinger W, Cantor SB, Cooksley

favour of LLLT applied with doses of 1–6 J per point in the

C (2007) Economic impact of palifermin on the costs of

oropharyngeal area in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy

hospitalization for autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplant:

or radiation therapy. There are limitations to the material in

analysis of phase 3 trial results. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 13(7):806–813

terms of small sample size in the included trials. However, the

11. Hwang WY, Koh LP, Ng HJ, Tan PH, Chuah CT, Fook SC et al (2004)

material was consistently in favour of LLLT in both in the

A randomized trial of amifostine as a cytoprotectant for patients

prevention of OM occurrences and reductions of severity,

receiving myeloablative therapy for allogeneic hematopoietic stem

pain, and duration of OM ulcers.

cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transpl 34:51–56

12. Lubart R, Eichler M, Lavi R, Friedman H, Shainberg A (2005)

Low-energy laser irradiation promotes cellular redox activity.

Acknowledgements Post-mortem to professor Anne Elisabeth

Photomed Laser Surg 23:3–9

Ljunggren for her encouragement and contribution to the early work

13. Rizzi CF, Mauriz JL, Freitas Correa DS, Moreira AJ, Zettler CG,

on this manuscript. Unfortunately, she was unable to see its

Filippin LI et al (2006) Effects of low-level laser therapy (LLLT) on

the nuclear factor (NF)-kappaB signaling pathway in traumatizedmuscle. Lasers Surg Med 38:704–713

Conflicts of interest None

14. Lopes-Martins RA, Marcos RL, Leonardo PS, Prianti AC Jr,

Muscara MN, Aimbire F et al (2006) Effect of low-level laser(Ga-Al-As 655 nm) on skeletal muscle fatigue induced byelectrical stimulation in rats. J Appl Physiol 101:283–288

15. Leal Junior EC, Lopes-Martins RA, Frigo L, De Marchi T, Rossi

RP, de Godoi V et al (2010) Effects of Low-level laser therapy(LLLT) in the development of exercise-induced skeletal muscle

1. Manas A, Palacios A, Contreras J, Sanchez-Magro I, Blanco P,

fatigue and changes in biochemical markers related to post-

Fernandez-Perez C (2009) Incidence of oral mucositis, its

exercise recovery. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 40(8):524–532

treatment and pain management in patients receiving cancer

16. Bjordal JM, Johnson MI, Iversen V, Aimbire F, Lopes-Martins RA

treatment at Radiation Oncology Departments in Spanish hospitals

(2006) Photoradiation in acute pain: a systematic review of

(MUCODOL Study). Clin Transl Oncol 11:669–676

possible mechanisms of action and clinical effects in randomized

2. Elting LS, Keefe DM, Sonis ST, Garden AS, Spijkervet FK,

placebo-controlled trials. Photomed Laser Surg 24:158–168

Barasch A et al (2008) Patient-reported measurements of oral

17. Bjordal JM, Johnson MI, Lopes-Martins RA, Bogen B, Chow R,

mucositis in head and neck cancer patients treated with

Ljunggren AE (2007) Short-term efficacy of physical interventions in

radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy: demonstration of

osteoarthritic knee pain. A systematic review and meta-analysis of

increased frequency, severity, resistance to palliation, and

randomised placebo-controlled trials. BMC Musculoskelet Disord

impact on quality of life. Cancer 113:2704–2713

3. Elting LS, Cooksley C, Chambers M, Cantor SB, Manzullo E,

18. Bjordal JM, Lopes-Martins RA, Joensen J, Ljunggren AE,

Rubenstein EB (2003) The burdens of cancer therapy. Clinical and

Couppe C, Stergioulas A et al (2008) A systematic review with

economic outcomes of chemotherapy-induced mucositis. Cancer

procedural assessments and meta-analysis of low level laser

therapy in lateral elbow tendinopathy (tennis elbow). BMC

4. Nonzee NJ, Dandade NA, Patel U, Markossian T, Agulnik M,

Musculoskelet Disord 9:75

Argiris A et al (2008) Evaluating the supportive care costs of

19. Chow RT, Johnson MI, Lopes-Martins RA, Bjordal JM (2009)

severe radiochemotherapy-induced mucositis and pharyngitis:

Efficacy of low-level laser therapy in the management of neck pain: a

results from a Northwestern University Costs of Cancer Program

systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo or

pilot study with head and neck and nonsmall cell lung cancer

active-treatment controlled trials. Lancet 374:1897–1908

patients who received care at a county hospital, a Veterans

20. Dickersin K, Scherer R, Lefebvre C (1994) Identifying relevant studies

Administration hospital, or a comprehensive cancer care center.

for systematic reviews. BMJ 309:1286–1291, 12 November 1994

Cancer 113:1446–1452

21. Cohen J (1977) Statistical power analysis for behavioural

5. Keefe DM, Schubert MM, Elting LS, Sonis ST, Epstein JB,

sciences. Academic, New York

Raber-Durlacher JE et al (2007) Updated clinical practice

22. Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJM,

guidelines for the prevention and treatment of mucositis.

Gavaghan DJ et al (1996) Assessing the quality of reports of

Cancer 109:820–831

randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Controlled Clin

6. Worthington HV, Clarkson JE, Eden OB (2007) Interventions for

preventing oral mucositis for patients with cancer receiving

23. Kjaergard LL, Als-Nielsen B (2002) Association between

treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. CD000978

competing interests and authors' conclusions: epidemiological

7. Lanzos I, Herrera D, Santos S, O'Connor A, Pena C, Lanzos E et

study of randomised clinical trials published in the BMJ. BMJ

al (2010) Mucositis in irradiated cancer patients: effects of an

antiseptic mouthrinse. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 15(5):e732–

24. Simoes A, Eduardo FP, Luiz AC, Campos L, Sa PH, Cristofaro M

et al (2009) Laser phototherapy as topical prophylaxis against

8. Lilleby K, Garcia P, Gooley T, McDonnnell P, Taber R, Holmberg

head and neck cancer radiotherapy-induced oral mucositis:

L et al (2006) A prospective, randomized study of cryotherapy

comparison between low and high/low power lasers. Lasers Surg

during administration of high-dose melphalan to decrease the

severity and duration of oral mucositis in patients with multiple

25. Shea B, Moher D, Graham I, Pham B, Tugwell P (2002) A comparison

myeloma undergoing autologous peripheral blood stem cell

of the quality of Cochrane reviews and systematic reviews published in

transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 37:1031–1035

paper-based journals. Eval Health Prof 25:116–129

Support Care Cancer (2011) 19:1069–1077

26. Antunes HS, Ferreira EM, de Matos VD, Pinheiro CT, Ferreira

33. Kuhn A, Porto FA, Miraglia P, Brunetto AL (2009) Low-level

CG (2008) The Impact of low power laser in the treatment of

infrared laser therapy in chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis: a

conditioning-induced oral mucositis: a report of 11 clinical cases

randomized placebo-controlled trial in children. J Pediatr Hematol

and their review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 13:E189–E192

27. Arun Maiya G, Sagar MS, Fernandes D (2006) Effect of low level

34. Schubert MM, Eduardo FP, Guthrie KA, Franquin JC, Bensadoun

helium-neon (He–Ne) laser therapy in the prevention & treatment

RJ, Migliorati CA et al (2007) A phase III randomized double-

of radiation induced mucositis in head and neck cancer patients.

blind placebo-controlled clinical trial to determine the efficacy of

Indian J Med Res 124:399–402

low level laser therapy for the prevention of oral mucositis in

28. Abramoff MM, Lopes NN, Lopes LA, Dib LL, Guilherme A,

patients undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation. Support

Caran EM et al (2008) Low-level laser therapy in the prevention

Care Cancer 15:1145–1154

and treatment of chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis in young

35. Kuhn A, Vacaro G, Almeida D, Machado A, Braghini PB, Shilling

patients. Photomed Laser Surg 26:393–400

MA et al (2007) Low-level infrared laser therapy for chemo- or

29. Bensadoun RJ, Franquin JC, Ciais G, Darcourt V, Schubert MM, Viot

radiation-induced oral mucositis: a randomized placebo-controlled

M et al (1999) Low-energy He/Ne laser in the prevention of radiation-

study. J Oral Laser Applications 7:175–181

induced mucositis. A multicenter phase III randomized study in

36. Chor A, Torres SR, Maiolino A, Nucci M (2010) Low-power laser

patients with head and neck cancer. Support Care Cancer 7:244–252

to prevent oral mucositis in autologous hematopoietic stem cell

30. Cowen D, Tardieu C, Schubert M, Peterson D, Resbeut M,

transplantation. Eur J Haematol 4:78–79

Faucher C et al (1997) Low energy helium–neon laser in the

37. Clarkson JE, Worthington HV, Furness S, McCabe M, Khalid T,

prevention of oral mucositis in patients undergoing bone marrow

Meyer S (2010) Interventions for treating oral mucositis for

transplant: results of a double blind randomized trial. Int J Radiat

patients with cancer receiving treatment. Cochrane Database Syst

Oncol Biol Phys 38:697–703

Rev 8:CD001973.

31. Genot-Klastersky MT, Klastersky J, Awada F, Awada A, Crombez

38. Albertini R, Villaverde AB, Aimbire F, Salgado MA, Bjordal JM,

P, Martinez MD et al (2008) The use of low-energy laser (LEL) for

Alves LP (2007) Anti-inflammatory effects of low-level laser

the prevention of chemotherapy- and/or radiotherapy-induced oral

therapy (LLLT) with two different red wavelengths (660 nm and

mucositis in cancer patients: results from two prospective studies.

684 nm) in carrageenan-induced rat paw edema. J Photochem

Support Care Cancer 16:1381–1387

Photobiol B 89(1):50–55

32. Cruz LB, Ribeiro AS, Rech A, Rosa LG, Castro CGJ, Brunetto

39. Brosseau L, Robinson V, Wells G, Debie R, Gam A, Harman K

AL (2007) Influence of low-energy laser in the prevention of oral

et al. (2005) Low level laser therapy (classes I, II and III) for

mucositis in children with cancer receiving chemotherapy. Pediatr

treating rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

Blood Cancer 48:435–440

Source: http://www.umc.br/artigoscientificos/art-cient-0052.pdf

Brother™ PocketJet® 6 Mobile Thermal Printers Home Healthcare Case Study PocketJet® 6 mobile thermal printers provide a better alternative to inkjets for the Midwest Pal iative & Hospice CareCenter. "We selected Brother On the heels of this mandate, new Electronic Moving forward, Midwest CareCenter plans to PocketJet® mobile

LAB #: U������������ CLIENT #: ����� PERCENTILE per g creatinine 2.5th 16th 50th 84th 97.5th 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) 3-Methoxytyramine (3-MT) Norepinephrine, free Epinephrine, free 5-Hydroxyindolacetic acid (5-HIAA) Phenethylamine (PEA) <dl: less than detection limit