Viagra gibt es mittlerweile nicht nur als Original, sondern auch in Form von Generika. Diese enthalten denselben Wirkstoff Sildenafil. Patienten suchen deshalb nach viagra generika schweiz, um ein günstigeres Präparat zu finden. Unterschiede bestehen oft nur in Verpackung und Preis.

Modulation of the startle reflex by pleasant and unpleasant music

International Journal of Psychophysiology 71 (2009) 37–42

Contents lists available at

International Journal of Psychophysiology

Modulation of the startle reflex by pleasant and unpleasant music

Mathieu Roy, Jean-Philippe Mailhot, Nathalie Gosselin, Sébastien Paquette, Isabelle Peretz

Department of Psychology, BRAMS, University of Montreal, Canada

Available online 23 July 2008

The issue of emotional feelings to music is the object of a classic debate in music psychology. Emotivistsargue that emotions are really felt in response to music, whereas cognitivists believe that music is only

representative of emotions. Psychophysiological recordings of emotional feelings to music might help to

resolve the debate, but past studies have failed to show clear and consistent differences between musical

excerpts of different emotional valence. Here, we compared the effects of pleasant and unpleasant musical

Startle reflexZygomatic

excerpts on the startle eye blink reflex and associated body markers (such as the corrugator and zygomatic

activity, skin conductance level and heart rate). The startle eye blink amplitude was larger and its latency was

shorter during unpleasant compared with pleasant music, suggesting that the defensive emotional system

was indeed modulated by music. Corrugator activity was also enhanced during unpleasant music, whereasskin conductance level was higher for pleasant excerpts. The startle reflex was the response that contributedthe most in distinguishing pleasant and unpleasant music. Taken together, these results provide strongevidence that emotions were felt in response to music, supporting the emotivist stance.

2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

techniques that are independent of voluntary subject control, such aspsychophysiological measures. Following this line of research,

The emotional power of music remains a mystery. Unlike most

compared the autonomic responses elicited by different

emotional inducers, music is not a sentient being nor does it seem to

musical emotions and found that sad, happy, and fearful music could

have any obvious adaptive value (Yet, most people

be differentiated by their autonomic activation patterns: Sad music

affirm that they feel strong emotions when they listen to music

was most strongly associated with changes in heart rate, blood

). This paradox led many music scholars to

pressure, skin conductance and skin temperature, fearful music was

believe that music is only iconic or representative of emotion, a

mostly associated with changes in the rate and amplitude of blood

position coined as ‘cognitivist' by . Opponents to this view,

flow, and happy music principally produced changes in respiratory

known as ‘emotivists', feel that the cognitivist position does not

activity and showed the highest skin conductance level (SCL).

render justice to the direct and unmediated fashion in which emotions

However, subsequent studies have failed to replicate many of these

are experienced by listeners (Although the debate is at a

findings. found that skin conductance responses

theoretical level, its resolution has practical implications for inter-

(SCR) were highest during the listening of fearful music,

preting music effects. Indeed, if music is only representative of

observed increased SCL during sad and fearful music

emotion, its therapeutic value could be seriously questioned. Studies

compared to happy music, and found higher SCL

measuring physiological, endocrine and brain responses to music as

during the listening of unpleasant compared to pleasant music.

indices of emotional reactivity have supported the emotivist view, but

Moreover, found higher heart rates during

the nature of these emotional responses and their resemblance with

unpleasant compared to pleasant music, whereas

emotions induced by other stimuli is unclear.

, and found theopposite. Therefore, there are inconsistent findings of the intensity and

1.1. Autonomic nervous system responses

direction of these autonomic responses between studies.

Such inconsistencies across psychophysiological emotion studies

In order to show that people not only recognize but feel emotions

are relatively common ), and the outcomes may

in response to music, emotional reactions should be measured by

be related to some context-bound patterns of actions that allow thesame emotion to be associated with a wide range of behavior andvarying patterns of somatovisceral activation ().

⁎ Corresponding author. Université de Montréal, Département de psychologie,

However, it should be noted that some psychophysiological measures

Pavillon Marie-Victorin, local D-418, 90 av. Vincent d'Indy, Montréal, QC, Canada H2V

appear more reliable than others. For example, respiration rate appears

E-mail address: (I. Peretz).

to be consistently higher during happy and fearful music than during

0167-8760/$ – see front matter 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

doi:

M. Roy et al. / International Journal of Psychophysiology 71 (2009) 37–42

brain activations alone do not allow for the distinction between

), although this effect may reflect differences

processes involved in emotional perception and emotional feeling.

in arousal that differentiate happiness and fear from sadness, and not

Physiological changes that affect the body and its responses are

musical emotions per se Indeed, cognitive

necessary to demonstrate the induction of emotional feelings.

theories of emotion have criticised the use of autonomic measures asindexes of felt emotions due to the non-specific nature of arousal

1.4. Present study

(For example, high arousal characterizesboth fear and happiness. Moreover, in music, arousal is known to be

Although these studies demonstrate that some emotions are felt in

mainly driven by its tempo ). The fact that

response to music, the results do not definitely refute the cognitivist

respiration rate has been linked to tempo through what appears to be a

viewpoint, as many psychophysiological responses are inconsistent,

general entrainment mechanism further contributes to discredit

and the responses that appear to induce the most stable responses

respiration rate as a clear index of musical emotions (

(e.g., respiration rate or hormonal responses) may be influenced by

). Although tempo is one of the main determinants of musical

other confounding factors, such as arousal or distraction. Finally, brain

emotions, musical emotions depend on many other factors than simple

imaging techniques cannot solely discriminate emotional feelings

tempo perception Thus, until the context-bound

from other aspects of emotional processing.

patterns of action that affect the autonomic responses to musical

In order to demonstrate the induction of emotional feelings,

emotions understood and controlled, more specific measures of

involuntary changes that affect the body and emotional processing

emotional reactions to music are needed to convince the sceptical

have to be observed in response to musical excerpts conveying dif-

cognitivist that music effectively induces emotions in the listener.

ferent emotions. In this context, the startle reflex is a good candidatemeasure, as it has been extensively and successfully used to probe

1.2. Hormonal responses

emotional reactions. It is an automatic defensive reaction to surprisingstimuli and can be measured by the magnitude of the eye blink

Neuroendocrine and hormonal responses constitute yet another

triggered by a loud white noise. As a response of the defensive

type of involuntary response that can be linked to emotional feelings.

emotional system, it is frequently used to test the efficacy of anxiolytic

Contrary to physiological responses, some hormones can be more

drugs ) or to explore emotional reactivity in

readily associated with positive or negative emotion (),

affective disorders (). In normal individuals, it is

such as cortisol with stress and negative emotions, or immunoglobin

typically enhanced by negative emotions and diminished by positive

A (S-IgA) with relaxation and positive emotions

ones, using pictures films or

). A few studies have found that listening to relaxing and pleasant

sounds () to induce emotions. The present

music was associated with lower levels of cortisol

study applied an affective startle modulation paradigm to musical

lower plasmatic levels of β-endorphins

stimuli and compared the effects of pleasant and unpleasant musical

(and higher mu-opiate receptor expression

excerpts on the acoustic startle blink reflex. If emotions are induced

(However, those studies only compared music

during music listening, then the startle reflex should be larger and of

with a silent control condition. Therefore, the observed effect may be

shorter latency during unpleasant music compared to pleasant music.

attributed to non-emotional aspects of the musical condition, such as

Moreover, in order to measure music effects on emotional

distraction. Indeed, when two musical conditions are compared, no

reactions, heart rate and skin conductance responses were also

differences were found between music inducing positive or negative

obtained along with facial expressions by assessing electromyographic

moods on levels of cortisol ), nor between up- or

(EMG) activity of the zygomaticus major (smiling) and the corrugator

down-lifting musical excerpts on levels of S-Iga, dopamine, norepine-

supercilii (frowning). Previous studies have shown that the activity of

phrenine, epinephrine or number of lymphocites

these muscles discriminated well between pleasant and unpleasant

suggesting that the differences previously observed

emotions elicited by pictures (Thus, it was expected

were mainly related to non-specific aspects of the task. One exception

that zygomatic activity would be higher during pleasant music, and

is the study by , who observed higher levels of β-

corrugator activity to be more noticeable during unpleasant music

endorphins, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), cortisol, norepi-

nephrine and growth hormone in youngsters listening to techno-music compared to classical music. However, these changes in

neuroendocrine responses appeared to be mainly linked to the higharousal induced by the techno-music, combined with the novelty-

2.1. Participants

seeking temperament of the participants. Neuroendocrine responses,although promising, appear to have the same limitations as autonomic

Sixteen participants (9F, 7M), aged between 20 and 40 years

(M = 25.1 ± 9.3 years) took part in this study. None were musicians, allreported fewer than five years of musical training, and none claimed

1.3. Brain imaging

any regular practice of a musical instrument.

Brain imaging techniques provide yet another way to measure

2.2. Musical excerpts

emotional reactions objectively. Studies using such techniques haveshown that pleasant emotional reactions to music activate regions

The musical excerpts used in this study were adapted from a prior

previously known to be involved in approach-related behaviors, such

study on pain modulation Three 100 s excerpts of

as the prefrontal cortex

pleasant music and three 100 s excerpts of unpleasant music were

), periacqueductal gray

selected from a pool of 30 musical excerpts. Each of the 30 excerpts had

matter and the nucleus accumbens

been previously evaluated by 20 independent participants on the

Negative emotions in

dimensions of valence (on a 0 = ‘pleasant' and 9=‘unpleasant') and

contrast activate regions involved in withdrawal-related behavior,

arousal (with 0 = ‘relaxing' and 9=‘stimulating'). Three highly pleasant

such as the parahippocampal gyrus (and amygdala

and three highly unpleasant excerpts were selected. Since unpleasant

(). Although these observations are fairly

excerpts were always judged to be arousing, all excerpts were selected in

consistent with activations observed with other emotional inducers,

the high range of arousal. Pleasant excerpts were judged to be more

M. Roy et al. / International Journal of Psychophysiology 71 (2009) 37–42

pleasant than unpleasant excerpts (mean valence for pleasant

averaged for each subject and musical condition. Facial EMG was

excerpts = 2.40, mean valence for unpleasant excerpts = 6.68; t(19)=

recorded over the left corrugator and zygomatic sites

5.58, p b 0.05) and did not differ in arousal (mean arousal for pleasant

using 8 mm Ag/AgCl shielded electrodes. Signals

excerpts = 5.00, mean arousal for unpleasant excerpts = 5.18; t (19)=

were bandpass filtered from 90 Hz to 1000 Hz and transformed using

1.535, n.s.). The selected pleasant excerpts were taken from the classical

the root mean square. Sampling rate was set at 1000 Hz. Area under

or jazz/pop repertoire and could be described as uplifting, with a rather

the curve of the rectified EMG signal were then extracted for the

fast tempo, such as the "Opening of William Tell" by Rossini. Unpleasant

corrugator and zygomatic muscle.

excerpts were mainly taken from the contemporary music repertoire.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) was recorded using a standard 3 lead

Examples of excerpts for each emotion category can be heard on our web

montage (Einthoven lead 2 configuration) (Biopac EL503). Instanta-

site at All selections were normalized

neous intervals between each R-wave of the ECG (RRI) were calculated

to equate loudness across musical excerpts by setting the peaks of the

from the ECG using a peak detection algorithm to detect successive R-

excerpts at 8% of the maximum volume allowed, using the normalisation

waves and obtain a continuous R–R tachogram. Careful examination of

option of the Cool Edit 2 sound editing software.

the ECG and the tachogram ensured that the automatic R-wave

The primary emotions (sadness, happiness, fear, anger, peacefulness

detection procedure had been performed correctly.

and surprise) and moods (anger, depression, fatigue, anxiety, vigor and

Skin conductance level (SCL) was recorded on the palmar surface of

confusion, as measured with the "profile of mood states", POMS;

the left hand, at the thenar and hypothenar eminences

), induced by those excerpts were also previously assessed

). The signal was smoothed and the mean SCL was calculated for

). Results showed that the primary emotions conveyed

the whole duration of each musical excerpt and averaged for the

by the excerpts were consistent with their emotional valence. Pleasant

pleasant and unpleasant music condition.

excerpts were associated with happiness whereas unpleasant ones wereassociated with fear and anger. Results on the mood questionnaire

confirmed these observations: The subscales for highly arousingnegative moods, such as anger and anxiety, were higher after listening

The physiological sensors were affixed while the participants sat

to the unpleasant excerpts, whereas the subscales for less arousing

comfortably in a quiet room. The pleasant and unpleasant excerpts

moods, such as depression, remained unaffected. Thus, the selected

were presented in a counterbalanced order across participants.

excerpts convey primary emotions and induce moods consistent with

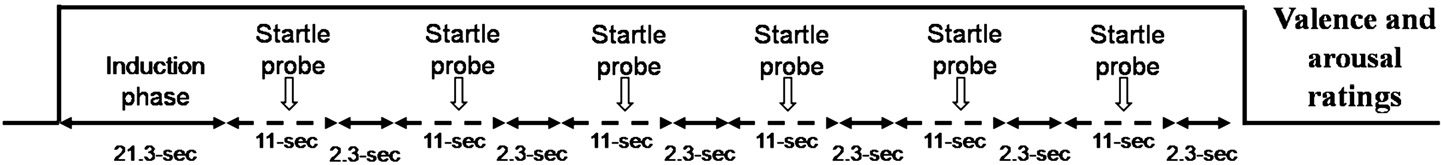

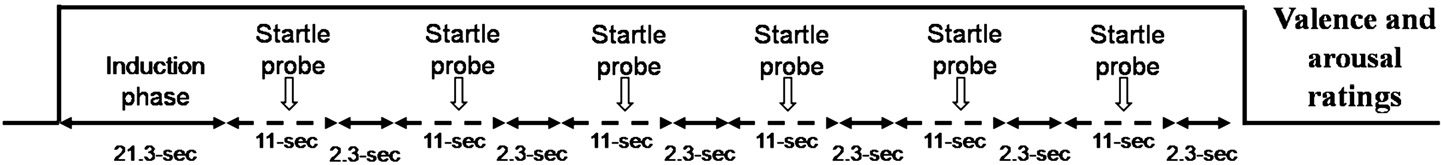

illustrates the procedure for one musical excerpt. Each musical excerpt

their positive or negative valence and their high level of arousal.

started with an emotional induction period of 21.3 s in which therewere no startle probes. The remaining 78.7 s were divided in six 11 s

2.3. Data collection and reduction

time window in which a startle probe occurred randomly. Each timewindow was separated by a period of 2.3 s in which no startle probe

Startle responses were elicited by a 100 dB SPL, 50 ms burst of

occurred. After each musical excerpt, the subject rated his/her

white noise, with instantaneous rise time. The acoustic startle probe

emotional reaction to the music on the dimensions of valence

was presented over Sony MDR-v200 headphones. The eye blink

(0 = unpleasant, 9 = pleasant) and arousal (0 = relaxing, 9 = stimulating).

component of the startle reflex was recorded electromyographicallyfrom the orbicularis oculi muscle beneath the left eye, using two

2.5. Data analysis

miniature 4 mm Ag/AgCl shielded electrodes placed 1.5 cm apart and asignal ground electrode placed on the forehead, following the

The musical excerpts were assessed statistically for the expected

guidelines of . The signal was amplified by

emotional effects by comparing the mean ratings of valence and

1000 and band-pass filtered at 90 Hz–500 Hz using a Biopac MP150

arousal. Sound intensity was assessed before each startle probe in both

System (Biopac Systems, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA). The sampling rate

musical conditions using RMS power preceding each startle probe for

was set at 1000 Hz. The amplified signal was then transformed using

the pleasant and unpleasant music conditions. After these control

the root mean square.

analyses, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted

The maximum amplitude and latency of each startle response were

to test for the effects of emotional condition (pleasant or unpleasant)

extracted from the data. Following the guidelines of

on the means of all the physiological measures used (startle blink reflex

, only responses for which the onset occurred between 21 and

amplitude and latency, corrugator and zygomatic activity, RRI and SCL).

120 ms from noise onset were considered as startle responses and

The MANOVA was followed by separate t-tests for each physiological

included in the analysis. The raw blink measurements were then

measure. Finally, a discriminant function analysis was conducted to

standardised within each subject to decrease variability due to

test if some patterns of physiological activation could reliably

differences in the absolute size of the startle blink across subjects,

discriminate between the pleasant and unpleasant musical conditions.

and expressed as T scores (50 + 10z), which yielded a mean of 50 and astandard deviation of 10 for each subject. The blink amplitudes and

latencies T scores were then averaged for the pleasant and unpleasantmusic condition.

3.1. Self-reported emotions

To assess the sound intensity of the musical excerpts prior to each

startle probe, the total root mean square amplitude (RMS) power was

The mean valence and arousal ratings were calculated for the

extracted for 1 s windows preceding each burst of white noise and

pleasant and unpleasant excerpts. The t-tests performed on these

Fig. 1. Distribution of startle probes during one musical excerpt. Participants listened passively to music for 21.3 s. In the last 78.7 s of the excerpts, six startle probes were randomlydelivered within 11 tie windows separated by periods of 2.3 s during which no probe could occur.

M. Roy et al. / International Journal of Psychophysiology 71 (2009) 37–42

average ratings confirmed that the intended emotions of the musical

excerpts were well recognized. The pleasant and unpleasant excerpts

Canonical variate correlation coefficients for the discriminant function

differed significantly on the dimension of valence (with a mean rating

Startle amplitude

of 8.49 and 1.91, respectively; t (15) = 13.04, p b 0.001). In contrast,

pleasant and unpleasant musical excerpts did not differ on the

Corrugator activity

dimension of arousal (with a mean rating of 6.41 and 7.50, respectively;

Zygomatic activity

Skin conductance level

t (15) = 1.79, n.s.).

3.2. Sound amplitude

condition (t (15) = 2.43, p b 0.05, η2 = 0.28). The physiological responses

The RMS power of the 1 s windows preceding each startle probe

were not limited to the 21.3 initial seconds without startle probes but

was equivalent for the pleasant (23.03 ± 0.68) and unpleasant (23.21 ±

were considered for the whole excerpt instead because only non-

0.49) musical excerpts (t (15) = 0.31, n.s.).

significant trends in the same direction were obtained on the initialpart of the musical excerpts.

3.3. Physiological measures

3.4. Discriminant analysis

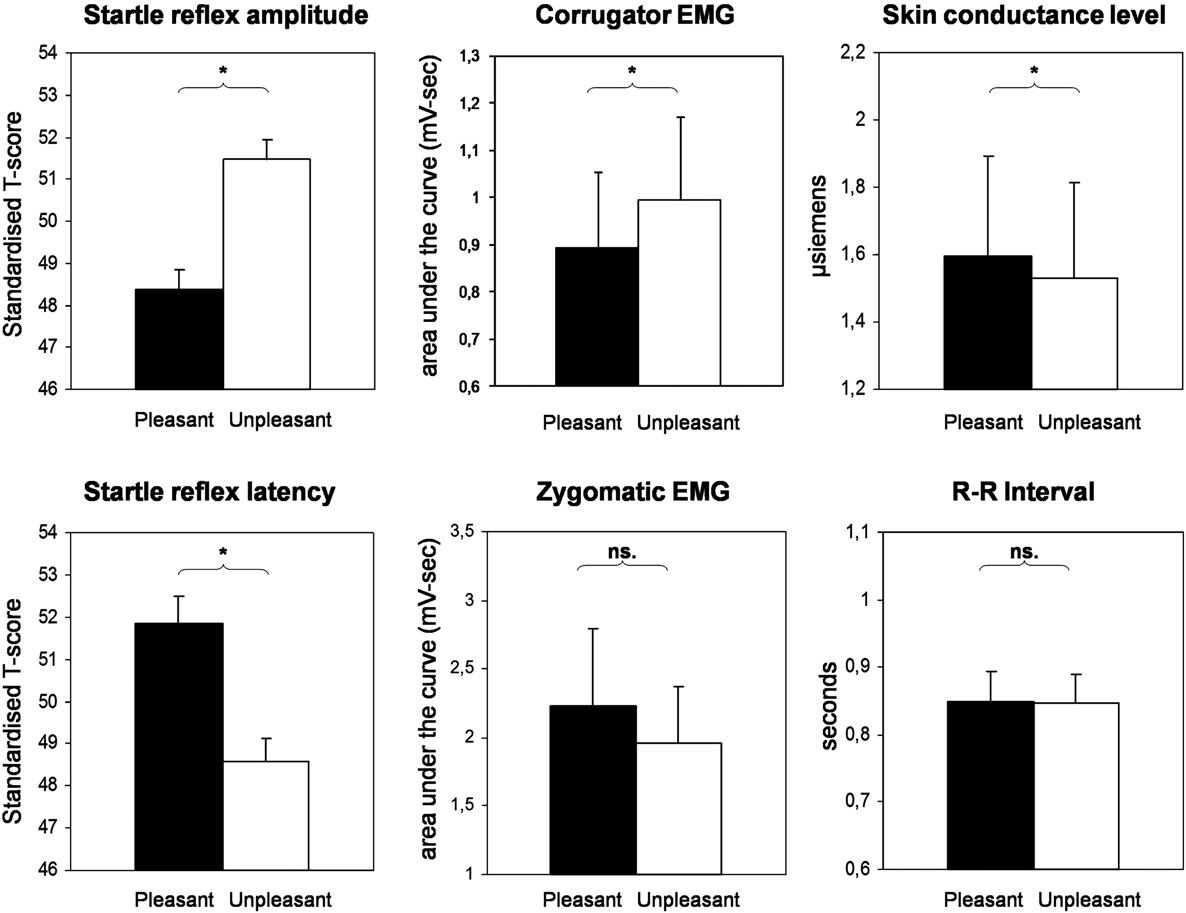

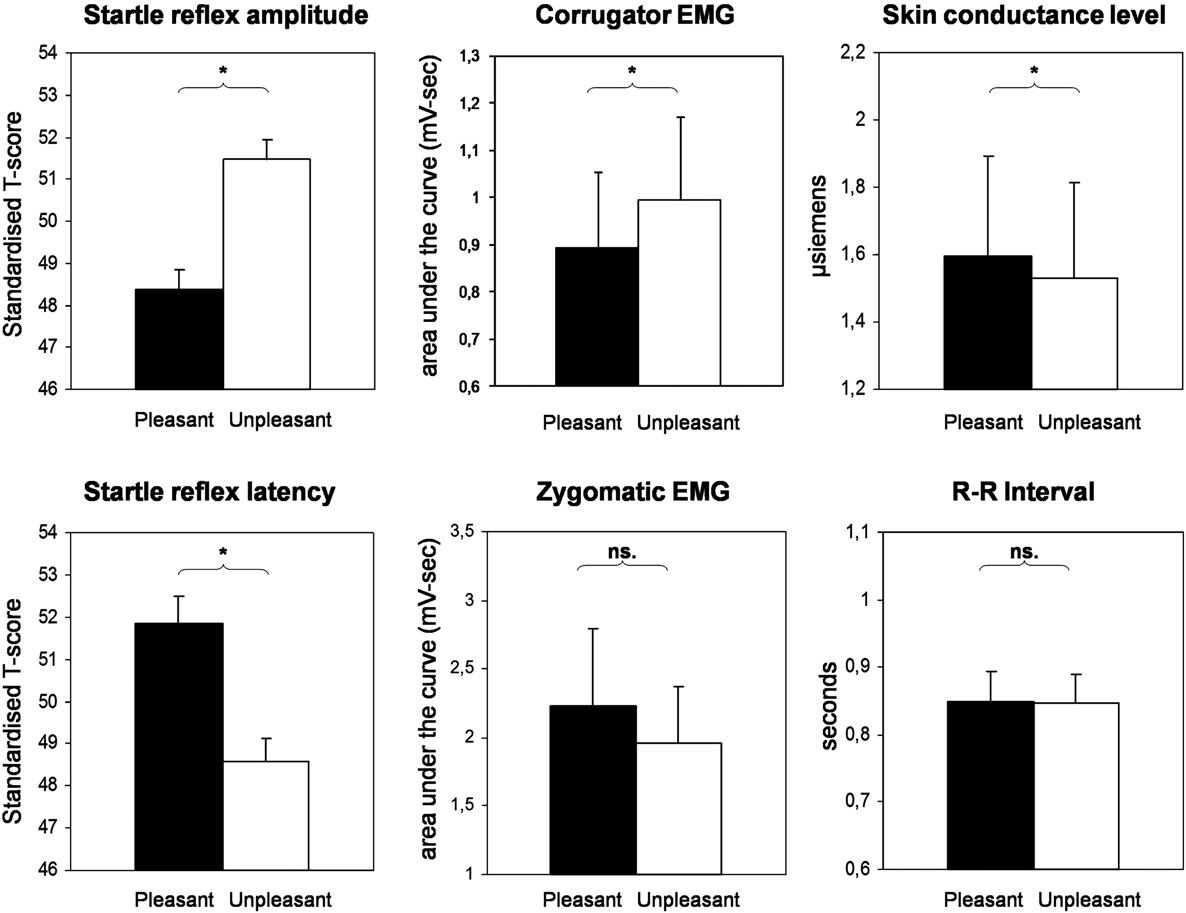

illustrates the mean values of each physiological measure for

the pleasant and unpleasant music condition. The results of the

The results of the discriminant analysis showed that the pleasant

MANOVA showed that the physiological responses were significantly

and unpleasant excerpts could easily be differentiated by a single

affected by the musical condition (F (6, 10) = 6.86, p b 0.01, η2 = 0.81).

function (Wilk's lambda (6) = 0.51, p b 0.01). This function correctly

The startle blink reflex was larger (t(15) = 3.35, p b 0.01, η2 = 0.43) and

classified pleasant excerpts in 75% of cases and unpleasant excerpts in

faster (t (15) = 2.81, p b 0.05, η2 = 0.35) during the unpleasant music as

87.5% of cases. summarizes the canonical variate correlation

compared to the pleasant music. Activity of the corrugator muscle was

coefficients of each physiological variable for the discriminant

higher during the unpleasant condition (t (15) = 2.79, p b 0.05, η2 =

function. These canonical variate correlation coefficients were much

0.34), but no significant difference in the activity of the zygomatic

more important for startle amplitude and latency compared to the

muscle was obtained between the two musical conditions (t (15) =

other physiological measures, indicating that the startle reflex was the

1.35, n.s., η2 = 0.11). RRI was also not affected by the valence of the

measure that contributed the most to the separation of the musical

musical excerpts (t (15) = 0.72, n.s., η2 = 0.03). In contrast, the SCL was

conditions. Although there is a lack of consensus regarding how high

found to be larger during the pleasant than the unpleasant music

correlations in a loading matrix should be interpreted, typically only

Fig. 2. Mean physiological responses for the pleasant and unpleasant musical conditions. Error bar represents one standard error above the mean. Significant differences (p b0.05) areindicated by asterisks. Note that error bars reflect the between-subjects variance in each condition whereas the results of the statistical tests reflect the within-subject contrast acrossexperimental conditions.

M. Roy et al. / International Journal of Psychophysiology 71 (2009) 37–42

variables with loadings of .32 and above are considered interpretable.

shown to be significantly modulated by the valence of the excerpt.

suggest that loadings over 0.71 are considered

This lack of sensitivity for zygomatic compared to corrugator activity

excellent, 0.63, very good, 0.55, good, 0.45, fair and 0.32, poor. In

is a common finding (perhaps because the

light of those guidelines, the canonical variates coefficients appear

zygomatic is implicated in some negative emotions such as disgust or

excellent for the startle reflex, but difficult to interpret for the other

that it is involved with display rules and other fine voluntary motor

Skin conductance, while having little contribution to the discrimi-

nant function, proved to be higher during the pleasant compared to theunpleasant excerpts. This finding adds to the controversy surrounding

4.1. Induction of emotional feelings by music

the interpretation of skin conductance changes in response to musicalemotion. The present findings are consistent with those of

The startle reflex was of higher amplitude and shorter latency

but inconsistent with and

during the listening of unpleasant in comparison with pleasant

. Moreover, the present findings are opposite to those generally

excerpts, suggesting that different emotional states were effectively

observed with other emotional induction techniques such as mental

induced by music. As the musical excerpts were manipulated to vary

imagery or the presentation of emotional movie clips for which SCL is

on the dimension of valence independently of arousal or loudness, the

higher during negatively valenced emotion This

observed effects are likely to reflect the induction of positive and

outcome suggests that skin conductance levels might be related to

negative emotional states in response to music, thereby supporting

some aspects of the emotional response that are not directly linked to

the emotivist's stance in contrast to critiques of cognitivists. First, the

the perceived valence and arousal and may vary from one study to

startle reflex is an involuntary response that does not depend on the

another. In the present case, the pleasant and arousing excerpts might

doubtful capacity of the subjects to adequately describe their own

have prompted motoric activity such as dancing or tapping of the foot.

experience. Second, the affective startle modulation effect is a reliable

Finally, no differences in heart rate were found between pleasant and

measure that avoids the important variability characterizing auto-

unpleasant excerpts. Taken together with the negative findings of

nomic nervous system measures. Moreover, startle modulation can be

and this lack of difference

ascribed to the emotional valence rather than arousal or attention,

suggests that heart rate alone is not sufficient to differentiate pleasant

thereby contrasting with prior studies. Third, because the modulation

from unpleasant musical conditions.

of the startle reflex indicates facilitation or inhibition of a motivationalpropensity to withdraw, it convincingly distinguishes the induction of

4.3. Implications

emotional states from the cold perception of emotional features. Thus,music appears to be as powerful as pictures (), films

The present study supports the emotivist stance and provides

or natural sounds to

some theoretical justifications for the use of music as a therapy. If

induce positive and negative emotions.

music is able to induce emotions that can reduce the activity of the

The absence of a neutral control condition complicates the

emotional defensive system, it can be used to alleviate some unpleas-

comparisons with studies using different inducers of emotion, since

ant emotional states, such as anxiety (), depression

it is difficult to tell if the startle modulation was due to an increase of

or pain (). In addition, the

the reflex during unpleasant music, a decrease of the reflex during

demonstration that emotions are indeed felt in response to music

pleasant music, or a combination of both. The absence of a neutral

also opens up questions about how and why it does so. The

control condition, however, was not incidental as it is difficult to find

combination of psychophysiological recordings with brain imaging

"neutral" music as judged by a majority of listeners. In addition, the

techniques, in addition to self-reported measures of emotion and

use of a silent control condition would not have been informative as

careful manipulation of the musical stimuli, will help to characterize

sound level by itself has been shown to influence the acoustic startle

how the brain and the body interact to create emotional feelings to

). Similarly, white noise matched with the musical

excerpts for sound amplitude could not have been a better controlcondition because white noise is generally experienced as unpleasant.

Nonetheless, a study using a similar design in which three startleprobes were delivered within 2-min long video clips, showed that

The work was supported by a grant from the Natural Science and

pleasant videos reduced the magnitude of the startle reflex compared

Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) to Isabelle Peretz,

to neutral videos, whereas unpleasant ones increased it (

and by a doctoral scholarship from the NSERC to Mathieu Roy. We

Hence, it is reasonable to assume that the present results

thank Amee Baird for English editing, Francine Giroux for statistical

depend on the effect of a combination of both facilitation and

advice and Pierre Rainville for his suggestions on physiological signal

inhibition of the defensive system. Nevertheless, the fact that the

startle reflex was modulated by the emotional valence of the excerptsis sufficient to attest that emotional states were induced by music.

Balaban, M.T., Losito, B.D.G., Simons, R.F., Graham, F.K., 1986. Off-line latency and

4.2. Startle reflex and physiological recordings as indices of felt emotion

amplitude scoring of the human reflex eye blink with Fortran IV. Psychophysiology23, 612–621.

In support to the idea that the startle reflex is one of the most

Barak, Y., 2006. The immune system and happiness. Autoimmunit. Rev. 5, 523–527.

reliable indices of emotional valence (the startle

Baumgartner, T., Esslen, M., Jancke, L., 2006. From emotion perception to emotion

experience: emotions evoked by pictures and classical music. Int. J. Psychophysiol.

reflex was the best response to discriminate between pleasant and

60, 34–43.

unpleasant musical excerpts. Corrugator activity was the second most

Blood, A.J., Zatorre, R.J., 2001. Intensely pleasurable responses to music correlate with

discriminative measure but was far behind the startle reflex. Although

activity in brain regions implicated in reward and emotion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.

98, 11818–11823.

its contribution to the discriminant function was minimal, the analysis

Blood, A.J., Zatorre, R.J., Bermudez, P., Evans, A.C., 1999. Emotional responses to pleasant

of variance showed that corrugator activity was significantly higher

and unpleasant music correlate with activity in paralimbic brain regions. Nat.

during the unpleasant excerpts compared to the pleasant excerpts,

Neurosci. 2, 382–387.

Blumenthal, T.D., Cuthbert, B.N., Filion, D.L., Hackley, S., Lipp, O.V., Van Boxtel, A., 2005.

confirming that positive and negative emotions were felt during the

Committee report: guidelines for human startle eyeblink electromyographic

listening of those excerpts. Zygomatic activity, however, was not

studies. Psychophysiology 42, 1–15.

M. Roy et al. / International Journal of Psychophysiology 71 (2009) 37–42

Bradley, M.M., Lang, P.J., 2000. Affective reactions to acoustic stimuli. Psychophysiology

Lang, P.J., Bradley, M.M., Cuthbert, B.N., 1990. Emotion, attention, and the startle reflex.

37, 204–215.

Psychol. Rev. 97, 377–395.

Cacioppo, J.T., Berntson, G.G., Larsen, J.T., Poehlmann, K.M., Ito, T.A., 2000. The

Lang, P.J., Bradley, M.M., Cuthbert, B.N., 1998. Emotion, motivation, and anxiety: brain

psychophysiology of emotion, In: Lewis, M., Haviland-Jones, J.M. (Eds.), The

mechanisms and psychophysiology. Biol. Psychiatry 44, 1248–1263.

Handbook of Emotion, 2nd Edition. Guilford Press, New York, pp. 173–191.

Larsen, J.T., Norris, C.J., Cacioppo, J.T., 2003. Effects of positive and negative affect on

Clark, L., Iversen, S.D., Goodwin, G.M., 2001. The influence of positive and negative mood

electromyographic activity over zygomaticus major and corrugator supercilii.

states on risk taking, verbal fluency and salivary cortisol. J. Affect. Disord. 63,

Psychophysiology 40, 776–785.

McKinney, C.H., Tims, F.C., Kumar, A.M., Kumar, M., 1997. The effect of selected classical

Comrey, A.L., Lee, H.B., 1992. A First Course in Factor Analysis, 2nd edition. Lawrence

music and spontaneous imagery on plasma beta-endorphin. J. Behav. Med. 20,

Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ. 442 pp.

Davies, S., 2001. Philosophical perspectives on music's expressiveness. In: Juslin, P.N.,

McNair, D., Lorr, M., Droppleman, L., 1992. EdITS manual for the profile of mood states

Sloboda, J.A. (Eds.), Music and emotion: theory and research. Oxford University

(POMS). EdITS/Educational and industrial Testing Service, San Diego, CA. 40 pp.

Press, pp. 23–44.

Menon, V., Levitin, D.J., 2005. The rewards of music listening: response and

Etzel, J.A., Johnsen, E.L., Dickerson, J., Tranel, D., Adolphs, R., 2006. Cardiovascular

physiological connectivity of the mesolimbic system. Neuroimage 28, 175–184.

and respiratory responses during musical mood induction. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 61,

Miluk-Kolasa, B., Obminski, Z., Stupnicki, R., Golec, L., 1994. Effects of music treatment

on salivary cortisol in patients exposed to pre-surgical stress. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol.

Fowles, D.C., Christie, M.J., Edelberg, R., Grings, W.W., Lykken, D.T., Venables, P.H., 1981.

102, 118–120.

Publication recommendations for electrodermal measurements. Psychophysiology

Nater, U.M., Abbruzzese, E., Krebs, M., Ehlert, U.l., 2006. Sex differences in emotional and

18, 232–239.

psychophysiological responses to musical stimuli. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 62, 300–308.

Franklin, J.C., Moretti, N.E.A., Blumenthal, T.D., 2007. Impact of stimulus signal-to-noise

Nyklicek, I., Thayer, J.F., Van Doornen, L.J.P., 1997. Cardiorespiratory differentiation of

ratio on prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle. Psychophysiology 44, 339–342.

musically-induced emotions. J. Psychophysiol. 11, 304–321.

Fridlund, A.J., Cacioppo, J.T., 1986. Guidelines for human electromyographic research.

Peretz, I., Gagnon, L., Bouchard, B., 1998. Music and emotion: perceptual determinants,

Psychophysiology 25, 567–589.

immediacy, and isolation after brain damage. Cognition 68, 111–141.

Gerra, G., Zaimovic, A., Franchini, D., Palladino, M., Giucastro, G., Reali, N., Maestri, D.,

Pinker, S., 1997. How the mind works. W. W. Norton & Company. 660 pp.

Caccavari, R., Delsignore, R., Brambilla, F., 1998. Neuroendocrine responses of

Roy, M., Peretz, I., Rainville, P., 2008. Emotional valence contributes to music-induced

healthy volunteers to ‘techno-music': relationships with personality traits and

analgesia. Pain 134, 140–147.

emotional state. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 28, 99–111.

Rudin, D., Kiss, A., Wetz, R.V., Sottile, V.M., 2007. Music in the endoscopy suite: a meta-

Gomez, P., Danuser, B., 2007. Relationship between musical structure and psychophy-

analysis of randomized controlled studies. Endoscopy 39, 507–510.

siological measures of emotion. Emotion 7, 377–387.

Sammler, D., Grigutsch, M., Fritz, T., Koelsch, S., 2007. Music and emotion: electro-

Grillon, C., Baas, J., 2003. A review of the modulation of the startle reflex by affective

physiological correlates of the processing of pleasant and unpleasant music.

states and its application in psychiatry. Clin. Neurophysiol. 114, 1557–1579.

Psychophysiology 44, 293–304.

Hirokawa, E., Ohira, H., 2003. The effects of music listening after a stressful task on

Schacter, S., Singer, J.E.,1962. Cognitive, social, and physiological determinants of emotional

immune functions, neuroendocrine responses, and emotional states in college

state. Psychol. Rev. 69, 379–399.

students. J. Music Ther. 40, 189–211.

Siedliecki, S.L., Good, M., 2006. Effect of music on power, pain, depression and disability.

Kaviani, H., Gray, J.A., Checkley, S.A., Raven, P.W., Wilson, G.D., Kumari, V., 2004.

J. Adv. Nurs. 54, 553–562.

Affective modulation of the startle response in depression: influence of the severity

Sloboda, J.A., O'Neill, S.A., 2001. Emotions in everyday listening to music. In: Juslin, P.N.,

of depression, anhedonia, and anxiety. J. Affect. Disord. 83, 21–31.

Sloboda, J.A. (Eds.), Music and emotion: theory and research. Oxford University

Khalfa, S., Peretz, I., Blondin, J., Robert, M., 2002. Event-related skin conductance

Press, pp. 415–429.

responses to musical emotions in humans. Neurosci. Lett. 328, 145–149.

Stefano, G.B., Zhu, W., Cadet, P., Salamon, E., Mantione, K.J., 2004. Music alters

Khalfa, S., Bella, S., Roy, M., Peretz, I., Lupien, S.J., 2003. Effects of relaxing music on

constitutively expressed opiate and cytokine processes in listeners. Med. Sci. Monit.

salivary cortisol level after psychological stress. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 999, 374–376.

10, 18–27.

Kivy, P., 1990. Music alone: Philosophical reflection on the purely musical experience.

Watanuki, S., Kim, Y.K., 2005. Physiological responses induced by pleasant stimuli.

Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY. 240 pp.

J. Physiol. Anthropol. Appl. Human Sci. 24, 135–138.

Koelsch, S., 2005. Investigating emotion with music: neuroscientific approaches. Ann. N.Y.

Winslow, J.T., Noble, P.L., Davis, M., 2007. Modulation of fear-potentiated startle and

Acad. Sci. 1060, 412–418.

vocalizations in juvenile rhesus monkeys by morphine, diazepam, and buspirone.

Koelsch, S., Fritz, T., V Cramon, D.Y., Muller, K., Friederici, A.D., 2006. Investigating

Biol. Psych. 61, 389–395.

emotion with music: an fMRI study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 27, 239–250.

Witvliet, C.V.O., Vrana, S.R., 2007. Play it again Sam: repeated exposure to emotionally

Krumhansl, C.L., 1997. An exploratory study of musical emotions and psychophysiology.

evocative music polarises liking and smiling responses, and influences other

Can. J. Exp. Psychol. 51, 336–353.

affective reports, facial EMG, and heart rate. Cogn. Emot. 21, 3–25.

Source: http://www.psy.gla.ac.uk/docs/download.php?type=PUBLS&id=2045

Webmail Um Ihre Emails immer und überall abzurufen, bietet Ihnen World4You das Webmail – ebenso haben Sie hier die Möglichkeit Ihre Email-Dienste zu verwalten. Bitte beachten Sie aber, dass Sie im Webmail nur Emails sehen können, die noch nicht durch ein anderes Emailprogramm (wie z.B. Microsoft Outlook) abgerufen wurden. Arbeiten Sie etwa zu Hause mit Outlook und wenn Sie unterwegs sind mit

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines NetworkPart of NHS Quality Improvement Scotland Autism spectrum disordersBooklet for parents and carers We would like to thank all the young people who took part in the focus groups to provide us with their ideas and illustrations for this booklet. © Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network ISBN 978 1 905813 27 8