Viagra gibt es mittlerweile nicht nur als Original, sondern auch in Form von Generika. Diese enthalten denselben Wirkstoff Sildenafil. Patienten suchen deshalb nach viagra generika schweiz, um ein günstigeres Präparat zu finden. Unterschiede bestehen oft nur in Verpackung und Preis.

Review article: vitamin d and inflammatory bowel diseases

Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics

Review article: vitamin D and inflammatory bowel diseases

V. P. Mouli* & A. N. Ananthakrishnan†,‡

*Department of Gastroenterology, All

India Institute of Medical Sciences,

New Delhi, India.

†

Harvard Medical School, Boston,

Vitamin D is traditionally associated with bone metabolism. The immuno-

‡Division of Gastroenterology,

logical effects of vitamin D have increasingly come into focus.

Massachusetts General Hospital,Boston, MA, USA.

AimTo review the evidence supporting a role of vitamin D in inflammatory

Correspondence to:

bowel diseases.

Dr A. N. Ananthakrishnan, Crohn's &Colitis Centre, Massachusetts General

Hospital, 165 Cambridge Street, 9th

A comprehensive search was performed on PubMed using the terms

Floor, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

crohn's disease' ‘ulcerative colitis' and ‘vitamin D'.

ResultsVitamin D deficiency is common in patients with inflammatory bowel dis-

eases (IBD) (16–95%) including those with recently diagnosed disease. Evi-

Submitted 27 September 2013

dence supports immunological role of vitamin D in IBD. In animal models,

First decision 15 October 2013

Resubmitted 26 October 2013

deficiency of vitamin D increases susceptibility to dextran sodium sulphate

Accepted 28 October 2013

colitis, while 1,25(OH)2D3 ameliorates such colitis. One prospective cohort

EV Pub Online 17 November 2013

study found low predicted vitamin D levels to be associated with anincreased risk of Crohn's disease (CD). Limited data also suggest an associ-

This commissioned review article wassubject to full peer review and the

ation between low vitamin D levels and increased disease activity, particu-

authors received an honorarium from

larly in CD. In a large cohort, vitamin D deficiency (<20 ng/mL) was

Wiley on behalf of AP&T.

associated with increased risk of surgery (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.2–2.5) in CDand hospitalisations in both CD (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.6–2.7) and UC (OR 2.3,95% CI 1.7–3.1). A single randomised controlled trial demonstrated thatvitamin D supplementation may be associated with reduced frequency ofrelapses in patients with CD compared with placebo (13% vs. 29%,P = 0.06).

ConclusionThere is growing epidemiological evidence to suggest a role for vitamin Ddeficiency in the development of IBD and also its influence on diseaseseverity. The possible therapeutic role of vitamin D in patients with IBDmerits continued investigation.

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39: 125–136

ª 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

V. P. Mouli and A. N. Ananthakrishnan

ciation with pathogenesis and natural history of these

Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD) consti-

tute chronic idiopathic inflammatory bowel diseases(IBD). The key underlying pathogenic mechanisms for

both diseases is a dysregulated host immune response to

A comprehensive literature search on Pubmed was con-

commensal intestinal flora in genetically susceptible indi-

ducted using the following search terms: ‘Crohn's dis-

viduals.1, 2 Known genetic variants incompletely explain

ease' ‘ulcerative colitis' and ‘vitamin D' to identify

the variance in disease incidence, suggesting a strong role

relevant English language articles published between

for environmental factors, supported by epidemiological

1966 and 2013. In addition, bibliographies of the

retrieved articles were searched to identify additional rel-

Vitamin D has long been recognised as a major regu-

evant articles.

lator of calcium and phosphorus metabolism and key inmaintaining bone health.5–7 However, several recent

studies have yielded new insights into the role of vitaminD in various other physiological processes. In particular,

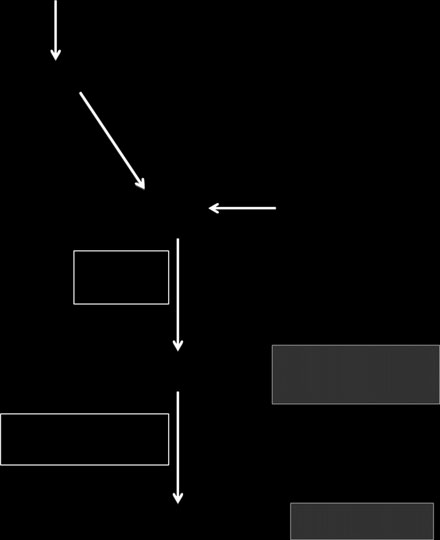

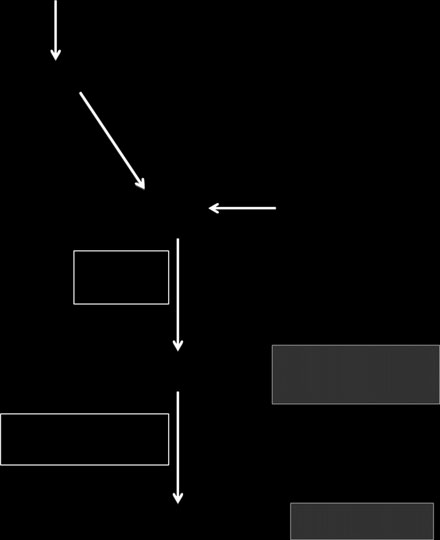

Vitamin D synthesis

vitamin D appears to play important roles in immune

The main source of vitamin D is endogenous production

regulation, particularly involving the innate immune

in the skin where ultraviolet B energy in the sunlight

system, cardiovascular and renal physiology, and devel-

converts 7-dehydrocholestrol to cholecalciferol (vitamin

opment of cancer.6 Importantly, an increasing body of

D3) (Figure 1).5, 14 Dietary contribution to vitamin D

literature supports an important role of vitamin D in the

status includes foods such as egg yolk, beef liver, cod

pathogenesis as well as potential therapy of IBD.8–13 The

liver oil, fatty fish, fortified milk and milk products.5

current review examines the evidence linking vitamin D

Vitamin D from the endogenous production on exposure

to IBD, both through its effect on bone health and asso-

to sunlight as well as that absorbed from diet is

7-dehydro cholesterol

UV exposure (Sunlight)

Dietary vitamin D

Major circulating form

25-hydroxy vitamin D3

(bound to vitamin D bindingprotein)

+ Parathormone (PTH)

(proximal tubules of kidney)

– Fibroblast growth factor 23

Figure 1 Metabolism of

Biologically active form

1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39: 125-136

ª 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Review: vitamin D and inflammatory bowel diseases

metabolised within the liver to 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25

related to the underlying bowel disease, while others are

(OH)D) by the enzyme vitamin D 25-hydroxylase. 25

in common with the non-IBD population. These include

(OH)D is the major circulating form of vitamin D and is

inadequate exposure to sunlight either related to lifestyle

also used to determine the status of vitamin D in clinical

or persistent symptoms of active disease restricting phys-

practice. 25(OH)D is biologically inactive and is activated

ical activity, inadequate dietary intake due to symptoms

within the proximal tubules of nephrons in the kidneys

of bowel disease, impaired absorption, impaired conver-

by the enzyme 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1alpha-hydroxylase

sion of vitamin D to its active products, increased catab-

(also known as CYP27B1) to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D

olism and increased excretion.5, 7 That inadequate

(1,25(OH)2D). The renal synthesis of the active biologi-

exposure to sunlight is an important cause of vitamin D

cal product of vitamin D (1,25(OH)2D) is regulated by

deficiency in patients with IBD is supported by evidence.

various factors including serum calcium and phosphorus

Several studies, particularly from northern climates, have

levels, parathormone and fibroblast growth factor 23.15

consistently demonstrated an association between vita-min D deficiency and winter season, a period of likely

Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in IBD

low sunlight and UVB exposure.13, 21, 22 Insufficient die-

While it is relatively easy to ascertain macronutrient

tary consumption also contributes to low vitamin D in

deficiency clinically, micronutrient deficiency may not

some patients with IBD. In a detailed nutritional survey

always be clinically evident and usually requires labora-

of 126 IBD patients, inadequate vitamin D consumption

tory testing. The best measure of an individual's vitamin

was found in 36% of patients and suboptimal serum

D status is serum 25(OH)D.5, 7, 16 Serum 25(OH)D lev-

vitamin D levels were found in 18% of patients.23 Oral

els of less than 20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L) indicate vitamin

intake correlated significantly with serum levels in CD

D deficiency. Serum 25(OH)D levels between 21 and

and with all IBD in remission.23 While other small stud-

29 ng/mL (52.5 and 72.5 nmol/L) represent vitamin D

ies suggested no correlation between dietary vitamin D

insufficiency, while levels between 30 and 100 ng/mL (75

intake and serum 25(OH)D in CD patients, they may

and 250 nmol/L) represent normal values.5, 7, 16 Several

have been limited by lack of statistical power.24

studies have reported a high prevalence of vitamin D

Fats and fat-soluble vitamins are absorbed after emul-

deficiency in patients with IBD, although it has not been

sification by bile acids. The bile acid pool is maintained

universally established that this rate is higher than in

by an enterohepatic circulation occurring from the ter-

other chronic illnesses, inflammatory diseases, or even

minal ileum. Interruption of the enterohepatic circulation

health individuals in that region (Table 1). Levin et al.

(e.g., by terminal ileal resection) could theoretically con-

reported vitamin D deficiency in 19% and insufficiency

tribute to vitamin D deficiency. However, clinical data in

in 38% of children with IBD in a cohort predominantly

support of this are conflicting. Terminal ileal resection

consisting of patients with CD.17 In contrast, Alkhouri

was associated with vitamin D deficiency in some stud-

et al. reported that the prevalence of vitamin D defi-

ies.25, 26 In a study of 12 CD patients who underwent

ciency in children with IBD (62%) was lower than the

terminal ileal resection, absorption of vitamin D was

rate in their controls (75%).18 In a large, retrospective

reduced with the decline in absorption correlating with

study of adult patients with IBD from Wisconsin (101

the length of the resected segment. However, other stud-

UC, 403 CD), nearly 50% of the patients had vitamin D

ies failed to identify an effect of ileal resection or active

deficiency and about 11% of patients had severe vitamin

disease.19 Malabsorption may theoretically contribute to

D deficiency,19 a frequency estimate that is consistent

low vitamin D in CD patients as vitamin D is absorbed

with other published IBD cohorts.13 While most studies

in the proximal part of small intestine. The prevalence of

have examined prevalence in patients with well estab-

vitamin D deficiency is higher in CD patients with upper

lished IBD, deficiency of vitamin D does not appear to

gastrointestinal tract involvement.27 However, when

be consequent to long-standing disease alone. In a

absorption of vitamin D was specifically tested, only 10%

cohort of newly diagnosed IBD patients from Manitoba

of patients with CD had decreased absorption of vitamin

providence in Canada, only 22% were found to have suf-

D compared to 50% of patients with pancreatic insuffi-

ficient levels of vitamin D.20

ciency.28 There also appears to be a wide variation inabsorption of vitamin D in patients with CD even in

Causes of vitamin D deficiency in patients with IBD

those with quiescent disease.29 Protein-losing enteropa-

There are several factors contributing to vitamin D defi-

thy occurs in some patients with IBD. As vitamin D and

ciency in patients with IBD, some causes specifically

its metabolites circulate predominantly as bound forms

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39: 125-136

ª 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

V. P. Mouli and A. N. Ananthakrishnan

Table 1 Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in unselected cohorts of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases

65% of patients had low serum 25(OH)D25% had levels below 10 ng/mL

27% of CD patients had 25(OH)D levels <30 nmol/L

15% of UC patients had 25(OH)D levels <30 nmol/L

Mean 25(OH)D was lower in IBD patients (18.7 mcg/L) compared with controls

(28.5 mcg/L) (P < 0.05)

16% of CD patients had vitamin D < 38 nmol/L

22% had 25(OH)D levels <40 nmol/L8% had 25(OH)D levels <25 nmol/L

27% of CD patients were deficient (25(OH)D < 10 ng/mL) compared to

During late-summer, 5% of controls and 18% of CD patients were deficient

During late-winter, 25% of controls and 50% of CD patients were deficient

50% were vitamin D deficient during winter (<50 nmol/L) and 19%

were deficient during summer

Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency (25(OH)D < 15 ng/mL) was 35%

88% had serum 25(OH)D levels below 75 nmol/L

Mean 25(OH) levels were lower in CD patients (11 ng/mL) compared with

those with UC (20 ng/mL) (P < 0.001)

25(OH)D levels were lower in CD patients (16 ng/mL) compared with controls

50% of patients had 25(OH)D < 30 ng/dL, 11% had levels below 10 ng/dL

Vitamin D insufficiency (<20 ng/mL) was seen in 31% of patients with CD

and 28% of UC patients

19% of patients were deficient in vitamin D (<51 nmol/L)

37% had vitamin D deficiency

63% of patients with CD were deficient (<50 nmol/L)

39% of the entire cohort had low vitamin D (<50 nmol/L); this was more

frequent in 43% of CD and 37% of UC patients

30% of patients with CD had levels below 37.5 nmol/L compared

to 37% of controls

95% of patients had deficient vitamin D levels (25(OH)D < 30 ng/mL)

28% had insufficient (20–30 ng/mL) and 32% had deficient (<20 ng/mL) levels

62% of patients had low vitamin D levels compared to 75% of controls

IBD, inflammatory bowel diseases; CD, Crohn's disease; UC, ulcerative colitis, IC, indeterminate colitis.

* Paediatric cohorts.

to plasma vitamin D binding protein (DBP), the loss of

tion study of nearly 30 000 individuals of European des-

DBP along with the bound vitamin D could be an addi-

cent, variants at three loci near the genes involved in

tional plausible mechanism of vitamin D deficiency, par-

cholesterol synthesis, vitamin D hydroxylation and vita-

ticularly in those with severe disease. Finally, recent

min D transport were associated with vitamin D insuffi-

studies have suggested that genetic variants contribute

ciency.30 The contribution of such genetic variants to

both to development of vitamin D insufficiency and

vitamin D status in patients with IBD has not yet been

response to supplementation. In a genome-wide associa-

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39: 125-136

ª 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Review: vitamin D and inflammatory bowel diseases

Role of vitamin D in bone turnover and mineral

Vitamin D and innate immunity

Vitamin D receptor is ubiquitously expressed in several

Vitamin D helps to maintain calcium homoeostasis by

human tissues including immune cells, keratinocytes,

acting on the small intestine epithelium and osteoblasts.

pancreatic beta-cells, cardiac myocytes, central nervous

1,25(OH)2D acts mainly through the nuclear vitamin D

system, renal tubules and the intestine. Many of these

receptor (VDR), which forms a heterodimer with a reti-

tissues also contain the enzymes for conversion of vita-

noid X receptor, binds to the vitamin D response ele-

min D to its active metabolites, supporting a widespread

ment and recruits co-activators and enzymes with

extraskeletal role of vitamin D.45 Vitamin D appears to

histone acetylation activity, thereby regulating gene

have an important role in innate immunity as well as

expression.10, 31–33 25(OH)D interacts with the VDR in

adaptive immunity.10, 33 It acts as a key link between

the small intestinal epithelium and augments the

toll-like receptor (TLR) activation and antibacterial

absorption of calcium and phosphorus from the small

responses in innate immunity. Activation of TLRs on

intestine.34 1,25(OH)2D also interacts with the VDR on

macrophages by a Mycobacterium tuberculosis derived

osteoblasts and increases the surface expression of

lipopeptide leads to upregulation of conversion of 25

Receptor Activator for Nuclear Factor jB ligand

(OH)D to the active 1,25(OH)2D, upregulation of VDR

(RANKL), which, after binding with RANK on pre-os-

expression and induction of downstream targets of VDR

teoclasts, converts them into osteoclasts.35, 36 Osteoclasts

including cathelicidin, an antimicrobial peptide.46 1,25

function in dissolution of bone matrix and mobilise cal-

(OH)2D also acts synergistically with activated NF-jB to

cium stores into circulation, thus helping in the mainte-

induce expression of b-defensin 4 gene.47 Supplementa-

nance of calcium homoeostasis. Dissolution of bone

tion with vitamin D in individuals with insufficient

matrix by osteoclasts is an essential part of bone

serum levels of 25(OH)D leads to induction of cathelici-

din, thus enhancing the innate immune defences against

Vitamin D deficiency leads to reduction in serum lev-

microbial agents.48

els of ionised calcium leading to secondary hyperpara-

Autophagy plays an important role in the pathogene-

sis of CD, and several lines of evidence support the

disproportionate increase in bone resorption, osteopenia

hypothesis that the effect of vitamin D on IBD patho-

and osteoporosis.37 In children, vitamin D deficiency

genesis may be through this pathway. 1,25 (OH)2D helps

results in poor mineralisation of the epiphyseal growth

in autophagy in macrophages by enhancing the co-locali-

plates leading to bone deformities and stunted longitudi-

sation of pathogen harbouring phagosomes with auto-

nal growth, which are the typical features of rickets. In

adults with vitamin D deficiency, there is defective min-

Similar induction of autophagy by vitamin D has also

eralisation of the newly formed bone collagen matrix

been demonstrated in several models of cancer cell lines.

resulting in osteomalacia which manifests as bone pain,

Vitamin D3 has been hypothesised to regulate autophagy

fractures and proximal muscle weakness.5, 7, 16

at several steps.50 Increased calcium absorption mediated

There is a high prevalence of metabolic bone disease

by the effect of vitamin D3 on the VDR can activate

in patients with IBD. The prevalence of osteopenia

autophagy through various calcium-dependent kinases

ranges from 23% to 67% and osteoporosis from 7% to

and phosphates, while vitamin D3 can itself downregu-

35% among patients with CD or UC.38–40 Active

late the expression of mTOR, a negative regulator of

inflammatory disease is a strong risk factor for low

autophagy.50, 51 Vitamin D3 can also induce autophagy

bone mineral density (BMD) in patients with IBD, with

through increasing beclin-1 expression, a regulatory of

BMD improving with increasing duration of remis-

autophagy, and activating the PI3K signalling path-

sion.41 This is supported by the known effect of TNF-a

way.50–52 Vitamin D has been long used to treat myco-

and other pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1, IL-6,

infections46, 53, 54

IL-17 in activating osteoclasts.42, 43 In addition, gluco-

supplementation may reduce likelihood of tuberculin

corticoids use is an important risk factor for bone loss

conversion.55, 56 In a randomised controlled trial, vita-

in patients with IBD.39 However, the data linking vita-

min D supplementation was associated with a reduced

min D deficiency and impaired BMD in patients with

rate of development of a positive tuberculin reaction,

IBD have been conflicting, with some studies support-

suggesting a protective effect against tuberculosis infec-

tion in an endemic population.56 Low serum vitamin D

effect.20, 39, 44

is also associated with reduced immunoreactivity to an

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39: 125-136

ª 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

V. P. Mouli and A. N. Ananthakrishnan

anergy panel, and supplementation with vitamin D in

link between polymorphisms in the VDR gene region on

anergic individuals with deficient levels restored delayed

chromosome 12 to development of IBD,10, 68–70 although

not all cohorts have yielded positive results. Variations

Vitamin D also plays a role in preventing over-activa-

in the DBP were also found to be associated with IBD.71

tion of pro-inflammatory responses. 1,25(OH)2D within

Few studies have been able to examine the association

the monocytes dose-dependently inhibits lipopolysaccha-

between vitamin D status and incident IBD directly. One

ride (LPS)-induced p38 phosphorylation and production

such study was using the Nurses' Health Study, a cohort

of IL-6 and TNF-a in LPS-stimulated monocytes.58 Anti-

of female registered nurses in the United States, followed

gen-presenting cells, including dendritic cells, express

prospectively using biennial questionnaires, and compre-

VDR.59 The action of 1,25(OH)2D on dendritic cells

hensive assessment of diet and supplement intake and

leads to a tolerogenic phenotype, thus protecting against

physical activity during the cohort follow-up timeline.8

autoimmune type 1 diabetes in adult non-obese diabetic

The vitamin D status of the participants was defined

mice.60 Maturation of dendritic cells is prevented by the

using a validated regression model incorporating race,

interaction of 1,25(OH)2D with VDR on the dendritic

diet, physical activity and region of residence. Over a

22-year follow-up, higher predicted plasma 25(OH)D le-ves was associated with a significant reduction in the risk

Vitamin D and adaptive immunity

of incident CD, but not UC.8 Compared to women with

Vitamin D receptor is expressed in mitotically active T

the lowest quartile of plasma vitamin D, those in highest

and B lymphocytes.62 1,25(OH)2D acts on helper T cells

quartile had a reduced risk of CD (HR 0.54, 95% CI

(TH cells), inhibits production of IL-2 and immunoglob-

0.30–0.99).8 For each 1 ng/mL increase in the plasma

ulin synthesis by TH cell regulated B lymphocytes.63 Reg-

level of 25(OH)D, there was a 6% relative risk reduction

ulatory T cells (Treg), which are responsible for

for CD. There was also an inverse association between

maintenance of tolerance to self-antigens, are also modu-

vitamin D intake from dietary sources and supplement

lated by 1,25(OH)2D.10, 33 Although the effect of vitamin

and the risk for incident UC; each 100 IU/day increase

D on B cells is predominantly through modulation of

in total vitamin D intake was associated with a 10% rela-

T-cell function, recent evidence suggests that 1,25

tive reduction in the risk of UC.8

(OH)2D may also act directly on the B cells, affectingthe proliferation of activated B cells and inhibiting the

Relationship of vitamin D levels and IBD disease

generation of plasma cells and post-switch memory B

In tune with its immune-modulating effects, vitamin Dmay also influence severity of inflammation in IBD.

Role of vitamin D in the immunopathogenesis of IBD

Vitamin D deficiency causes more severe growth retarda-

Several lines of epidemiological and laboratory evidence

tion and weight loss and also led to higher mortality in

support a role for vitamin D in the pathogenesis of IBD.

IL-10 KO mice colitis.72 Disease severity correlated with

First, there is a north–south gradient in IBD incidence, a

vitamin D status in mice with DSS-induced colitis; both

gradient that parallels UV exposure and consequently

local as well as endocrine effects of 1,25 (OH)2D affect

vitamin D levels. In a study by Khalili et al., residence in

the disease severity.73 TNF-a plays a central role in

Southern latitudes of the United States, particularly at

inflammation. 1,25(OH)2D reduces the severity of colitis

age 30 was associated with a significantly lower risk of

in IL-10 KO mice by downregulating several genes asso-

CD [Hazard ratio (HR) 0.48, 95% CI 0.30–0.77] and UC

ciated with TNF-a.74 When mice with tri-nitro-benzene

(HR 0.62, 95% CI 0.42–0.90).65 This has been supported

sulphonic (TNBS) acid-induced colitis were treated with

by other studies that have modelled residential UV expo-

a combination of corticosteroids and 1,25 (OH)2D, the

sure and shown an inverse correlation between UV

improvement in disease activity paralleled downregula-

exposure and IBD incidence.66 Mice lacking VDR are

tion of TH1 inflammatory cytokines profile as well as

more susceptible to dextran sodium sulphate (DSS)-in-

TH17 effector functions along with the promotion of TH2

duced mucosal injury compared with the wild type

and regulatory T-cell profiles.75

mice.67 The disruption in the epithelial junctions was

Data supporting a clinical association between vitamin

severe in mice lacking VDR and 1,25(OH)2D preserved

D deficiency and disease activity in IBD are conflicting

the integrity of the tight junctions in Caco-2 cells mono-

(Table 2). Neither El-Matary et al. nor Levin et al. found

layers.67 Genetic epidemiological studies have suggested a

a correlation between vitamin D levels and disease

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39: 125-136

ª 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Review: vitamin D and inflammatory bowel diseases

Table 2 Observational studies of the association between vitamin D levels and outcomes in Crohn's disease andulcerative colitis

negatively correlatedwith disease activity(correlationco-efficient

Vitamin D levels were

not associated with

Vitamin D deficiency

was associated with l

ower HRQoL( 2.2, 95% CI

increased diseaseactivity (1.1, 95%CI 0.4–1.7) in CD,but not in UC

Vitamin D deficiency

(<20 ng/mL) was

increased risk ofsurgery (OR 1.8,95% CI 1.2–2.5) inCD and hospitalisationsin both CD (OR 2.1,95% CI 1.6–2.7) andUC (OR 2.3, 95%CI 1.7–3.1)

Patients with low

within 3 months of

anti-TNF initiation

increased risk of

early cessation of

CD, Crohn's disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; HBI, Harvey Bradshaw index; PCDAI, Paediatric Cro-hn's disease activity index; PUCAI, paediatric ulcerative colitis activity index; SCCAI, simple clinical colitis activity index.

activity in cross-sectional studies of IBD cohorts.17, 76 In

increased risk of surgery [Odds ratio (OR) 1.76; 95% CI

contrast, a retrospective study by Ulitsky et al. concluded

1.24–2.51] and hospitalisation (OR 2.07; 95% CI 1.59–

that vitamin D deficiency was associated with lower heal-

2.68) compared with those with sufficient levels.13 Fur-

th-related quality of life and increased disease activity in

thermore, CD patients who normalised their plasma 25

patients with CD, but not with UC.19 Overcoming some

(OH)D had a reduced likelihood of IBD-related surgery

of the limitations engendered by cross-sectional assess-

(OR 0.56; 95% CI 0.32–0.98) compared with those who

ment of vitamin D and disease severity, we examined

remained deficient.13

prospectively the association between vitamin D defi-ciency and need for IBD-related surgery or hospitalisa-

Does vitamin D have a role in the treatment of IBD

tions in a large cohort of 3217 patients with at least one

There have been several studies examining the role of vita-

measurement of plasma 25(OH)D.13 We found that

min D as a therapeutic agent for IBD in animal models.77

plasma 25(OH)D < 20 ng/mL was associated with an

Vitamin D-deficient IL-10 KO mice spontaneously

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39: 125-136

ª 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

V. P. Mouli and A. N. Ananthakrishnan

develop an accelerated and severe form of IBD. However,

of anti-TNF treatment, with a more pronounced effect

when such mice were fed high-calcium diet and 1,25

on patients with CD.79 Miheller et al. compared the

(OH)2D, they developed only mild disease.72 Both in

therapeutic effects of 1,25(OH)2D and 25(OH) D in

TNBS- and DSS-induced colitis models, administration of

patients with CD with respect to disease activity and

1,25(OH)2D led to an improvement in disease activity and

bone health.80 There was a significant improvement in

addition of 1,25(OH)2D to a steroid regimen had a syner-

disease activity as well as bone metabolism in the short-

gistic effect and this combination most effectively reduced

term at 6 weeks with 1,25(OH)2D but not 25(OH)D.80

the disease severity.78 A novel vitamin D analogue withanti-proliferative effects and limited calcemic activity was

also found to alleviate disease activity in mice withDSS-induced colitis.78

There have been few human studies (Table 3). Jorgen-

Despite emerging promising data, there exist several lim-

sen et al. conducted a multicentre, randomised, dou-

itations in the literature regarding the role of vitamin D

ble-blind, placebo-controlled trial in Denmark evaluating

in IBD pathogenesis. First, while consistently supported

the efficacy of 1,25(OH)2D as a maintenance therapy in

by experimental animal models, the association between

CD patients in remission.12 One hundred and eight

low pre-diagnosis vitamin D and increased risk of CD

patients were randomised to receive either 1200 IU of

has been examined in a single prospective cohort study

1,25(OH)2D with 1200 mg of calcium or 1200 mg of cal-

that used a regression model to predict an individual's

cium alone daily over 1 year. Nearly one-third of the

vitamin D status. Ongoing analysis of pre-diagnosis

study population had vitamin D deficiency defined as

banked specimens from ongoing prospective cohorts as

serum 25(OH)D levels <50 nmol/L. Only 13% of

well as additional high-risk IBD cohorts will provide a

patients in the vitamin D group relapsed during the

more definitive answer to this hypothesis as randomised

1-year study period compared to 29% in the placebo

controlled trials of vitamin D in prevention of IBD are

group (P = 0.06).12 A second study by Zator et al. exam-

unlikely to be feasible, given relatively low incidence of

ined the influence of vitamin D status on response to

disease in the general population, and need for large

anti-TNF therapy. In a single centre cohort of patients

numbers of participants and long follow-up. The associa-

with CD and UC, plasma 25(OH)D levels measured

tion between low vitamin D and increased disease

within 3 months of initiation of anti-TNF therapy dem-

activity, particularly in CD, is also supported primarily

onstrated a significant inverse association with durability

Table 3 Interventional studies examining the effect of vitamin D supplementation on disease activity in Crohn'sdisease and ulcerative colitis

Number of patients

Mean CDAI decreased

patients treated with

of cholecalciferol

104 CD patients in

Relapse rate was lower

clinical remission

in patients treated with

compared to placebo(29%) (P = 0.06)

Vitamin D supplementation

mild-to-moderate CD

reduced CDAI scores from

230 to 118 (P < 0.0001), and

improved health-related

serum 25(OH)Dof 40 ng/mL

CD, Crohn's disease; CDAI, Crohn's disease activity index.

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39: 125-136

ª 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Review: vitamin D and inflammatory bowel diseases

cross-sectional and unable to differentiate effect of vita-

three regimens for 6 weeks: 2000 IU daily of vitamin D2;

min D on disease activity from that of disease course on

2000 IU daily of vitamin D3; or 50 000 IU weekly of

vitamin D levels, more recent analyses of large cohorts

vitamin D2.83 It was found that the 6-week regimens of

have been able to prospectively demonstrate an associa-

50 000 IU of vitamin D2 per week and 2000 IU of vita-

tion between low vitamin D levels and increased risk for

min D3 daily were superior to vitamin D2 2000 IU daily.

surgery and hospitalisations, particularly in CD.13 How-

Whereas the regimen of 50 000 IU per week of vitamin

ever, only one randomised controlled trial has examined

D2 improved the serum 25(OH)D levels to more than

the role of vitamin D in preventing relapse, but was also

32 ng/mL in 75% of patients, only 38% of patients who

limited by small numbers.12 Effect of vitamin D supple-

received 2000 IU of vitamin D3 daily and 25% of patients

mentation in ameliorating disease activity in CD has

who received 2000 IU of vitamin D2 daily achieved

been examined only in two open-label pilot studies, and

serum 25(OH)D levels of more 32 ng/mL after 6 weeks

no studies have evaluated this in UC. Consequently,

of therapy. All the three regimens were found to be safe

there is an urgent need for high-quality randomised

and well tolerated.

intervention trials of vitamin D supplementation in bothCD and UC with disease activity as a treatment end

Future directions

Several unanswered question remain regarding the role ofvitamin D in IBD (Table 4). Further investigation is

Clinical practice

needed to understand the effects of dietary intake of vita-

Patients with IBD are at risk of developing vitamin D

min D and vitamin D supplementation in relation to poly-

deficiency. The Endocrine Clinical Practice Guidelines

morphisms of DBP or VDR to identify if there are

Committee recommends screening of patients with IBD

subgroups who may derive greater benefit from prophy-

as well as patients who are on corticosteroids for vitamin

laxis or who would require greater doses for treatment.

D status.16 While there is lack of professional guidelines

With recent evidence pointing towards vitamin D defi-

regarding subsequent assessments of vitamin D status, we

ciency as associated with IBD risk, confirmation of such

adopt the following in our practice. If the baseline vita-

findings in other cohorts would establish the vitamin D as

min D status is normal, it may be logical to consider

one of the links in the gene-environment-gut micro-

rechecking the status annually or biennially if there is

biome-immune system interactions necessary for the

active disease, if there is documented metabolic bone

development of IBD. It also merits investigation whether

disease or if there is continued use of systemic corticos-teroids. The Institute of Medicine and the Endocrine

Table 4 Unanswered clinical questions regarding the

Practice Guidelines Committee recommend a dietary

role of vitamin D in inflammatory bowel diseases

intake of 400 IU of vitamin D per day for infants, 600 IUof vitamin D per day for children beyond 1 year of age

1. Does low serum vitamin D cause Crohn's disease or

ulcerative colitis, or is it a marker for other risk factors?

and adults and 800 IU of vitamin D per day for the

2. Can supplementation with vitamin D in high-risk individuals

elderly aged above 70 years.82 However, to consistently

prevent or delay the onset of Crohn's disease or

raise the level of 25(OH)D to more than 30 ng/mL, espe-

ulcerative colitis?

cially in patients who are at risk for vitamin D deficiency,

3. Does vitamin D deficiency cause a more severe phenotype

or increased inflammatory activity in Crohn's disease,

the Endocrine Practice Guidelines Committee recom-

or is it merely a consequence of severity of disease? Is

mended that a maintenance dose of at least 1000 IU per

vitamin D status predictive of recurrence of Crohn's

day would be required.16 To treat documented vitamin D

deficiency, it is recommended to use either vitamin D2 or

4. What is the optimal role of vitamin D supplementation as a

vitamin D3 in a dosage of 2000 IU per day for 6 weeks,

therapeutic modality in patients with IBD?

Induction of remission?

or 50 000 IU once a week for 6 weeks in case of children

Maintenance of remission and prevention of relapse?

and vitamin D2 or vitamin D3 6000 IU per day for

Prevention of post-operative recurrence?

8 weeks, or 50 000 IU once a week for 8 weeks for adults

5. What is the optimal serum 25(OH)D level for its effect

to achieve serum 25(OH)D levels of more than 30 ng/

on inflammation in patients with IBD?

mL. The optimal therapeutic regimen in IBD patients

6. What is the optimal dose and modality for treatment of

was examined in a single clinical trial by Pappa et al. in

vitamin D deficiency in IBD patients?

which 71 patients with IBD aged 5–21 years with vitamin

7. Can vitamin D supplementation reduce risk of

colorectal cancer in IBD?

D deficiency were randomised to one of the following

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39: 125-136

ª 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

V. P. Mouli and A. N. Ananthakrishnan

vitamin D deficiency leads causally to increased disease

severity or is merely a consequence of severe disease. Fur-

Guarantor of the article: Ananthakrishnan.

thermore, it needs to be identified if there are high-risk

Author contributions: Mouli and Ananthakrishnan per-

groups of patients who may need to be screened for vita-

formed literature review. Mouli wrote the first draft of

min D deficiency and preemptively treated to prevent the

the manuscript. Ananthakrishnan provided supervision

onset of IBD. Further high-quality studies are needed to

and both authors approved the final version of the

evaluate if correction of vitamin D deficiency or if vitamin

D supplementation can prevent disease relapses, whetherit can be used to induce remission in active disease, and

whether it has a role in prevention of long-term dis-

Declaration of personal interests: Dr Ananthakrishnan

ease-related complications like colorectal cancer as has

has served on the scientific advisory board of Cubist

been identified in non-IBD patients. Continued and fertile

interactions between biochemists, nutritional epidemiolo-

Declaration of funding interests: Dr Ananthakrishnan is

gists, laboratory scientists and clinical researchers will help

supported in part by a grant from the National Insti-

address many of these unanswered questions, improve our

tutes of Health (K23 DK097142). This work is also sup-

understanding of the role of the complex panoply of

ported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (P30

functions of vitamin D, and its application into clinical

DK043351) to the Center for Study of Inflammatory

Bowel Diseases.

10. Cantorna MT, Zhu Y, Froicu M, Wittke

guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab

A. Vitamin D status, 1,25-

2011; 96: 1911–30.

1. Abraham C, Cho JH. Inflammatory

dihydroxyvitamin D3, and the immune

17. Levin AD, Wadhera V, Leach ST, et al.

bowel disease. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:

system. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 80:

Vitamin D deficiency in children with

inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci

2. Khor B, Gardet A, Xavier RJ. Genetics

11. Garg M, Lubel JS, Sparrow MP, Holt

2011; 56: 830–6.

and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel

SG, Gibson PR. Review article: vitamin

18. Alkhouri RH, Hashmi H, Baker RD,

disease. Nature 2011; 474: 307–17.

D and inflammatory bowel disease –

Gelfond D, Baker SS. Vitamin and

3. Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, et al.

established concepts and future

mineral status in patients with

Host-microbe interactions have shaped

directions. Aliment Pharmacol Ther

inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr

the genetic architecture of inflammatory

2012; 36: 324–44.

Gastroenterol Nutr 2013; 56: 89–92.

bowel disease. Nature 2012; 491:

12. Jorgensen SP, Agnholt J, Glerup H,

19. Ulitsky A, Ananthakrishnan AN, Naik

et al. Clinical trial: vitamin D3

A, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in

4. Ananthakrishnan AN. Environmental

treatment in Crohn's disease – a

patients with inflammatory bowel

triggers for inflammatory bowel disease.

randomized double-blind placebo-

disease: association with disease activity

Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2013; 15: 302.

controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol

and quality of life. JPEN J Parenter

5. Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N

Ther 2010; 32: 377–83.

Enteral Nutr 2011; 35: 308–16.

Engl J Med 2007; 357: 266–81.

13. Ananthakrishnan AN, Cagan A, Gainer

20. Leslie WD, Miller N, Rogala L,

6. Holick MF. Sunlight and vitamin D for

VS, et al. Normalization of plasma 25-

Bernstein CN. Vitamin D status and

bone health and prevention of

hydroxy vitamin D is associated with

bone density in recently diagnosed

autoimmune diseases, cancers, and

reduced risk of surgery in Crohn's

inflammatory bowel disease: the

cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr

disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013; 19:

Manitoba IBD Cohort Study. Am J

2004; 80: 1678S–88S.

Gastroenterol 2008; 103: 1451–9.

7. Rosen CJ. Clinical practice. Vitamin D

14. Norman AW. From vitamin D to

21. Gilman J, Shanahan F, Cashman KD.

insufficiency. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:

hormone D: fundamentals of the

Determinants of vitamin D status in

vitamin D endocrine system essential

adult Crohn's disease patients, with

8. Ananthakrishnan AN, Khalili H,

for good health. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;

particular emphasis on supplemental

Higuchi LM, et al. Higher predicted

88: 491S–9S.

vitamin D use. Eur J Clin Nutr 2006;

vitamin D status is associated with

15. Bienaime F, Prie D, Friedlander G,

60: 889–96.

reduced risk of Crohn's disease.

Souberbielle JC. Vitamin D metabolism

22. McCarthy D, Duggan P, O'Brien M,

Gastroenterology 2012; 142: 482–9.

and activity in the parathyroid gland.

et al. Seasonality of vitamin D status

9. Cantorna MT, Mahon BD. Mounting

Mol Cell Endocrinol 2011; 347:

and bone turnover in patients with

evidence for vitamin D as an

Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol

environmental factor affecting

16. Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-

Ther 2005; 21: 1073–83.

autoimmune disease prevalence. Exp

Ferrari HA, et al. Evaluation, treatment,

23. Vagianos K, Bector S, McConnell J,

Biol Med (Maywood) 2004; 229:

and prevention of vitamin D deficiency:

Bernstein CN. Nutrition assessment of

an Endocrine Society clinical practice

patients with inflammatory bowel

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39: 125-136

ª 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Review: vitamin D and inflammatory bowel diseases

disease. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr

36. Yasuda H, Shima N, Nakagawa N,

responses. J Immunol 2009; 182: 4289–

2007; 31: 311–9.

et al. Osteoclast differentiation factor is

24. Harries AD, Brown R, Heatley RV,

a ligand for osteoprotegerin/

49. Yuk JM, Shin DM, Lee HM, et al.

Williams LA, Woodhead S, Rhodes J.

osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and

Vitamin D3 induces autophagy in

Vitamin D status in Crohn's disease:

is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proc

human monocytes/macrophages via

association with nutrition and disease

Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998; 95: 3597–

cathelicidin. Cell Host Microbe 2009; 6:

activity. Gut 1985; 26: 1197–203.

25. Tajika M, Matsuura A, Nakamura T,

37. Lips P. Vitamin D deficiency and

50. Wu S, Sun J. Vitamin D, vitamin D

et al. Risk factors for vitamin D

secondary hyperparathyroidism in the

receptor, and macroautophagy in

deficiency in patients with Crohn's

elderly: consequences for bone loss and

inflammation and infection. Discov Med

disease. J Gastroenterol 2004; 39: 527–33.

fractures and therapeutic implications.

2011; 11: 325–35.

26. Leichtmann GA, Bengoa JM, Bolt MJ,

Endocr Rev 2001; 22: 477–501.

51. Wang J, Lian H, Zhao Y, Kauss MA,

Sitrin MD. Intestinal absorption of

38. Ardizzone S, Bollani S, Bettica P,

Spindel S. Vitamin D3 induces

cholecalciferol and 25-

Bevilacqua M, Molteni P, Bianchi Porro

autophagy of human myeloid leukemia

hydroxycholecalciferol in patients with

G. Altered bone metabolism in

cells. J Biol Chem 2008; 283: 25596–

both Crohn's disease and intestinal

inflammatory bowel disease: there is a

resection. Am J Clin Nutr 1991; 54:

difference between Crohn's disease and

52. Sly LM, Lopez M, Nauseef WM, Reiner

ulcerative colitis. J Intern Med 2000;

NE. 1alpha,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3-

27. Sentongo TA, Semaeo EJ, Stettler N,

247: 63–70.

induced monocyte antimycobacterial

Piccoli DA, Stallings VA, Zemel BS.

39. Bernstein CN, Leslie WD. Review

activity is regulated by

Vitamin D status in children, adolescents,

article: osteoporosis and inflammatory

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and

and young adults with Crohn disease. Am

bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther

mediated by the NADPH-dependent

J Clin Nutr 2002; 76: 1077–81.

2004; 19: 941–52.

phagocyte oxidase. J Biol Chem 2001;

28. Vogelsang H, Schofl R, Tillinger W,

40. Siffledeen JS, Fedorak RN, Siminoski K,

276: 35482–93.

Ferenci P, Gangl A. 25-hydroxyvitamin

et al. Bones and Crohn's: risk factors

53. Liu PT, Modlin RL. Human

D absorption in patients with Crohn's

associated with low bone mineral

macrophage host defense against

disease and with pancreatic

density in patients with Crohn's

Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Curr Opin

insufficiency. Wien Klin Wochenschr

disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2004; 10:

Immunol 2008; 20: 371–6.

1997; 109: 678–82.

54. Liu PT, Stenger S, Tang DH, Modlin RL.

29. Farraye FA, Nimitphong H, Stucchi A,

41. Reffitt DM, Meenan J, Sanderson JD,

Cutting edge: vitamin D-mediated

et al. Use of a novel vitamin D

Jugdaohsingh R, Powell JJ, Thompson

human antimicrobial activity against

bioavailability test demonstrates that

RP. Bone density improves with disease

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is dependent

vitamin D absorption is decreased in

remission in patients with inflammatory

on the induction of cathelicidin.

patients with quiescent Crohn's disease.

bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol

J Immunol 2007; 179: 2060–3.

Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011; 17: 2116–21.

Hepatol 2003; 15: 1267–73.

55. Arnedo-Pena A, Juan-Cerdan JV,

30. Wang TJ, Zhang F, Richards JB, et al.

42. Kong YY, Feige U, Sarosi I, et al.

Romeu-Garcia A, et al. Latent

Common genetic determinants of

Activated T cells regulate bone loss and

tuberculosis infection, tuberculin skin

vitamin D insufficiency: a genome-wide

joint destruction in adjuvant arthritis

test and vitamin D status in contacts of

association study. Lancet 2010; 376:

through osteoprotegerin ligand. Nature

tuberculosis patients: a cross-sectional

1999; 402: 304–9.

and case-control study. BMC Infect Dis

31. Kim S, Shevde NK, Pike JW. 1,25-

43. Redlich K, Hayer S, Ricci R, et al.

2011; 11: 349.

Dihydroxyvitamin D3 stimulates cyclic

Osteoclasts are essential for TNF-alpha-

56. Ganmaa D, Giovannucci E, Bloom BR,

vitamin D receptor/retinoid X receptor

mediated joint destruction. J Clin Invest

et al. Tuberculin skin test conversion,

DNA-binding, co-activator recruitment,

2002; 110: 1419–27.

and latent tuberculosis in Mongolian

and histone acetylation in intact

44. Jahnsen J, Falch JA, Mowinckel P,

school-age children: a randomized,

osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Res 2005; 20:

Aadland E. Vitamin D status,

parathyroid hormone and bone mineral

feasibility trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;

32. McDonnell DP, Pike JW, O'Malley BW.

density in patients with inflammatory

96: 391–6.

The vitamin D receptor: a primitive

bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol

57. Toss G, Symreng T. Delayed

steroid receptor related to thyroid

2002; 37: 192–9.

hypersensitivity response and vitamin D

hormone receptor. J Steroid Biochem

45. Zehnder D, Bland R, Williams MC,

deficiency. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 1983;

1988; 30: 41–6.

et al. Extrarenal expression of 25-

53: 27–31.

33. Cantorna MT, Mahon BD. D-hormone

hydroxyvitamin d(3)-1 alpha-

58. Zhang Y, Leung DY, Richers BN, et al.

and the immune system. J Rheumatol

hydroxylase. J Clin Endocrinol Metab

Vitamin D inhibits monocyte/

Suppl 2005; 76: 11–20.

2001; 86: 888–94.

macrophage proinflammatory cytokine

34. Christakos S. Recent advances in our

46. Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, et al. Toll-like

production by targeting MAPK

understanding of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin

receptor triggering of a vitamin D-

phosphatase-1. J Immunol 2012; 188:

D(3) regulation of intestinal calcium

mediated human antimicrobial

absorption. Arch Biochem Biophys 2011;

response. Science 2006; 311: 1770–3.

59. Brennan A, Katz DR, Nunn JD, et al.

523: 73–6.

47. Liu PT, Schenk M, Walker VP, et al.

Dendritic cells from human tissues

35. Takeda S, Yoshizawa T, Nagai Y, et al.

Convergence of IL-1beta and VDR

express receptors for the

Stimulation of osteoclast formation by

activation pathways in human TLR2/1-

immunoregulatory vitamin D3

1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D requires its

induced antimicrobial responses. PLoS

binding to vitamin D receptor (VDR)

ONE 2009; 4: e5810.

Immunology 1987; 61: 457–61.

in osteoblastic cells: studies using VDR

48. Adams JS, Ren S, Liu PT, et al.

60. Adorini L, Penna G, Giarratana N,

knockout mice. Endocrinology 1999;

Vitamin D-directed rheostatic

Uskokovic M. Tolerogenic dendritic

140: 1005–8.

regulation of monocyte antibacterial

cells induced by vitamin D receptor

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39: 125-136

ª 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

V. P. Mouli and A. N. Ananthakrishnan

ligands enhance regulatory T cells

murine inflammatory bowel disease.

three regimens. J Clin Endocrinol Metab

inhibiting allograft rejection and

J Nutr 2000; 130: 2648–52.

2012; 97: 2134–42.

autoimmune diseases. J Cell Biochem

73. Liu N, Nguyen L, Chun RF, et al.

84. Driscoll RH Jr, Meredith SC, Sitrin M,

2003; 88: 227–33.

Altered endocrine and autocrine

Rosenberg IH. Vitamin D deficiency

61. Griffin MD, Lutz W, Phan VA,

metabolism of vitamin D in a mouse

and bone disease in patients with

Bachman LA, McKean DJ, Kumar R.

model of gastrointestinal inflammation.

Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 1982;

Dendritic cell modulation by 1alpha,25

Endocrinology 2008; 149: 4799–808.

83: 1252–8.

dihydroxyvitamin D3 and its analogs: a

74. Zhu Y, Mahon BD, Froicu M, Cantorna

85. Lamb EJ, Wong T, Smith DJ, et al.

vitamin D receptor-dependent pathway

MT. Calcium and 1 alpha,25-

Metabolic bone disease is present at

that promotes a persistent state of

dihydroxyvitamin D3 target the TNF-

diagnosis in patients with inflammatory

immaturity in vitro and in vivo. Proc

alpha pathway to suppress experimental

bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther

Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001; 98: 6800–5.

inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J

2002; 16: 1895–902.

62. Provvedini DM, Tsoukas CD, Deftos LJ,

Immunol 2005; 35: 217–24.

86. Siffledeen JS, Siminoski K, Steinhart H,

Manolagas SC. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin

75. Daniel C, Sartory NA, Zahn N, Radeke

Greenberg G, Fedorak RN. The

D3 receptors in human leukocytes.

HH, Stein JM. Immune modulatory

frequency of vitamin D deficiency in

Science 1983; 221: 1181–3.

treatment of trinitrobenzene sulfonic

adults with Crohn's disease. Can J

63. Lemire JM, Adams JS, Kermani-Arab V,

acid colitis with calcitriol is associated

Gastroenterol 2003; 17: 473–8.

Bakke AC, Sakai R, Jordan SC. 1,25-

with a change of a T helper (Th) 1/Th17

87. Pappa HM, Gordon CM, Saslowsky

Dihydroxyvitamin D3 suppresses human

to a Th2 and regulatory T cell profile. J

TM, et al. Vitamin D status in children

T helper/inducer lymphocyte activity in

Pharmacol Exp Ther 2008; 324: 23–33.

and young adults with inflammatory

vitro. J Immunol 1985; 134: 3032–5.

76. El-Matary W, Sikora S, Spady D. Bone

bowel disease. Pediatrics 2006; 118:

64. Chen S, Sims GP, Chen XX, Gu YY,

mineral density, vitamin D, and disease

Chen S, Lipsky PE. Modulatory effects

activity in children newly diagnosed

88. Kuwabara A, Tanaka K, Tsugawa N,

of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on human

with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig

et al. High prevalence of vitamin K and

B cell differentiation. J Immunol 2007;

Dis Sci 2011; 56: 825–9.

D deficiency and decreased BMD in

179: 1634–47.

77. Narula N, Marshall JK. Management of

inflammatory bowel disease. Osteoporos

65. Khalili H, Huang ES, Ananthakrishnan

inflammatory bowel disease with

Int 2009; 20: 935–42.

AN, et al. Geographical variation and

vitamin D: beyond bone health. J

89. Joseph AJ, George B, Pulimood AB,

incidence of inflammatory bowel

Crohns Colitis 2012; 6: 397–404.

Seshadri MS, Chacko A. 25(OH) vitamin

disease among US women. Gut 2012;

78. Verlinden L, Leyssens C, Beullens I,

D level in Crohn's disease: association

61: 1686–92.

et al. The vitamin D analog TX527

with sun exposure & disease activity.

66. Nerich V, Jantchou P, Boutron-Ruault

ameliorates disease symptoms in a

Indian J Med Res 2009; 130: 133–7.

MC, et al. Low exposure to sunlight is a

chemically induced model of

90. Pappa HM, Langereis EJ, Grand RJ,

risk factor for Crohn's disease. Aliment

inflammatory bowel disease. J Steroid

Gordon CM. Prevalence and risk

Pharmacol Ther 2011; 33: 940–5.

Biochem Mol Biol 2013; 136: 107–11.

factors for hypovitaminosis D in young

67. Kong J, Zhang Z, Musch MW, et al.

79. Zator ZA, Cantu SM, Konijeti GG, et al.

patients with inflammatory bowel

Novel role of the vitamin D receptor in

Pre-treatment 25-hydroxy vitamin D

disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr

maintaining the integrity of the

levels and durability of anti-tumor

2011; 53: 361–4.

intestinal mucosal barrier. Am J Physiol

necrosis factor a therapy in

91. Atia A, Murthy R, Bailey BA, et al.

Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2008; 294:

inflammatory bowel diseases. JPEN J

Vitamin D status in veterans with

Parenter Enteral Nutr 2013 [Epub ahead

inflammatory bowel disease:

68. Dresner-Pollak R, Ackerman Z, Eliakim

relationship to health care costs and

R, Karban A, Chowers Y, Fidder HH.

80. Miheller P, Muzes G, Hritz I, et al.

services. Mil Med 2011; 176: 711–4.

The BsmI vitamin D receptor gene

Comparison of the effects of 1,25

92. Suibhne TN, Cox G, Healy M,

polymorphism is associated with

dihydroxyvitamin D and 25

O'Morain C, O'Sullivan M. Vitamin D

ulcerative colitis in Jewish Ashkenazi

hydroxyvitamin D on bone pathology

deficiency in Crohn's disease:

patients. Genet Test 2004; 8: 417–20.

and disease activity in Crohn's disease

prevalence, risk factors and supplement

69. Naderi N, Farnood A, Habibi M, et al.

patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009; 15:

use in an outpatient setting. J Crohns

Association of vitamin D receptor gene

Colitis 2012; 6: 182–8.

polymorphisms in Iranian patients with

81. Yang L, Weaver V, Smith JP, Bingaman

93. Fu YT, Chatur N, Cheong-Lee C, Salh

inflammatory bowel disease. J

S, Hartman TJ, Cantorna MT.

B. Hypovitaminosis D in adults with

Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 23: 1816–22.

Therapeutic effect of vitamin D

inflammatory bowel disease: potential

70. Simmons JD, Mullighan C, Welsh KI,

supplementation in a pilot study of

role of ethnicity. Dig Dis Sci 2012; 57:

Jewell DP. Vitamin D receptor gene

Crohn's patients. Clin Transl

polymorphism: association with

Gastroenterol 2013; 4: e33.

94. Laakso S, Valta H, Verkasalo M,

Crohn's disease susceptibility. Gut 2000;

82. Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, et al.

Toiviainen-Salo S, Viljakainen H,

47: 211–4.

The 2011 report on dietary reference

Makitie O. Impaired bone health in

71. Eloranta JJ, Wenger C, Mwinyi J, et al.

intakes for calcium and vitamin D from

inflammatory bowel disease: a case-

Association of a common vitamin D-

the Institute of Medicine: what

control study in 80 pediatric patients.

binding protein polymorphism with

clinicians need to know. J Clin

Calcif Tissue Int 2012; 91: 121–30.

inflammatory bowel disease. Pharma-

Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96: 53–8.

95. Hassan V, Hassan S, Seyed-Javad P,

cogenet Genomics 2011; 21: 559–64.

83. Pappa HM, Mitchell PD, Jiang H, et al.

et al. Association between Serum 25

72. Cantorna MT, Munsick C, Bemiss C,

Treatment of vitamin D insufficiency in

(OH) Vitamin D concentrations and

children and adolescents with

inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs)

Dihydroxycholecalciferol prevents and

inflammatory bowel disease: a

activity. Med J Malaysia 2013; 68: 34–8.

ameliorates symptoms of experimental

randomized clinical trial comparing

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39: 125-136

ª 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Source: http://www.observatoire-crohn-rch.fr/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Vit-D-IBD-APT-2014.pdf

January 1, 2016At A Glance For Active Employees, Retirees, Vestees and Dependent Survivors, Enrollees covered under Preferred List Provisions, their enrolled Dependents, and for COBRA Enrollees and Young Adult Option Enrollees enrolled through Participating Agencies with Empire Plan benefits This guide briefly describes Empire Plan benefits. It is not a complete description and is subject to change. For a complete description of your benefits and your responsibilities, refer to your Empire Plan Certificate and all Empire Plan Reports and Certificate Amendments. For information regarding your NYSHIP eligibility or enrollment, contact your agency Health Benefits Administrator (HBA). If you have questions regarding specific benefits or claims, contact the appropriate Empire Plan administrator. (See page 23.)

A community-based factorial trial on Alzheimer's disease. Effects of expectancy, recruitment methods, co- morbidity and drug use. The Dementia Study in Northern Norway Fred Andersen, MD ‘Navigare necesse est. Vivere non est necesse' Pompeius 56 f. Kr Contents